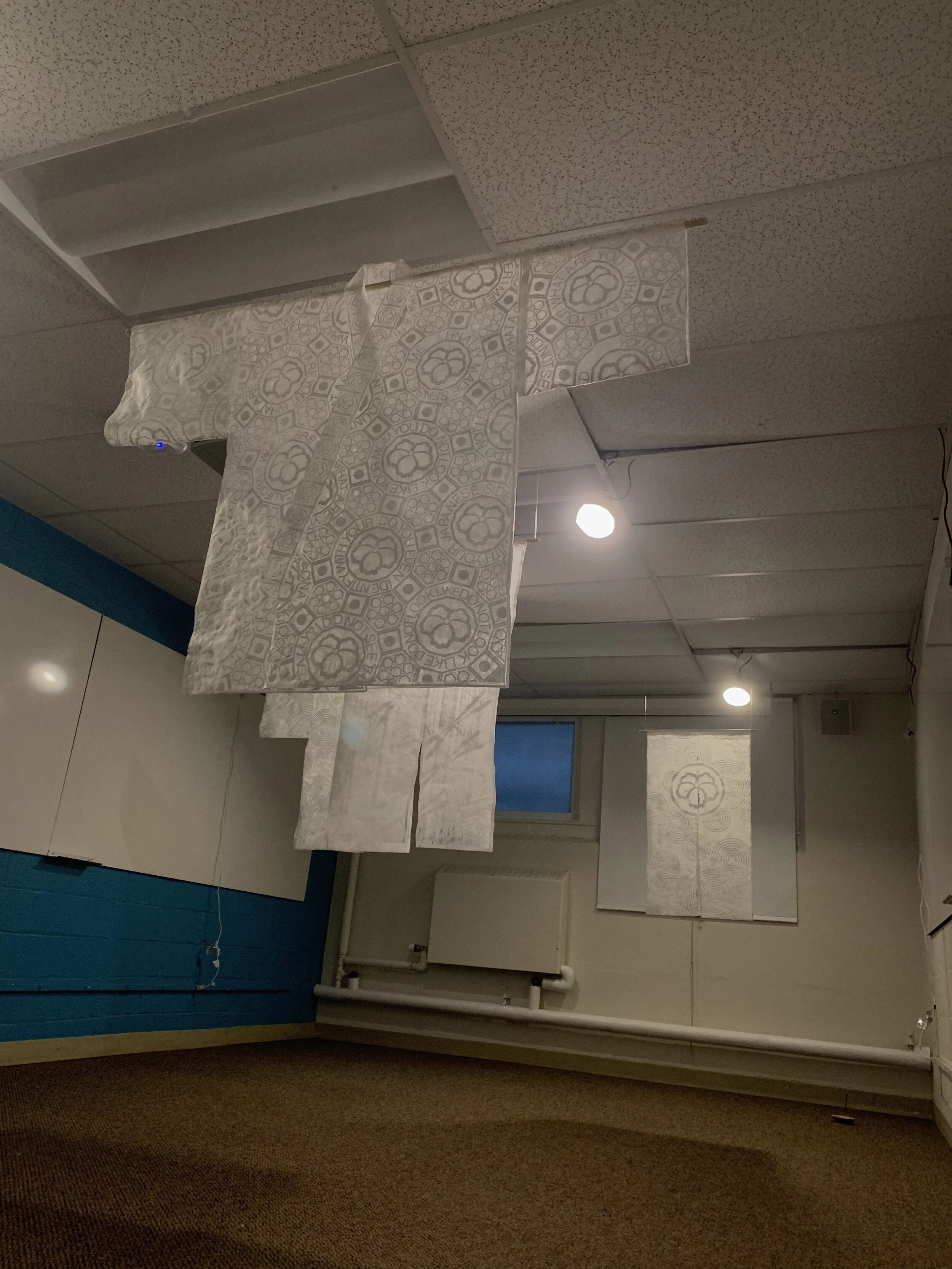

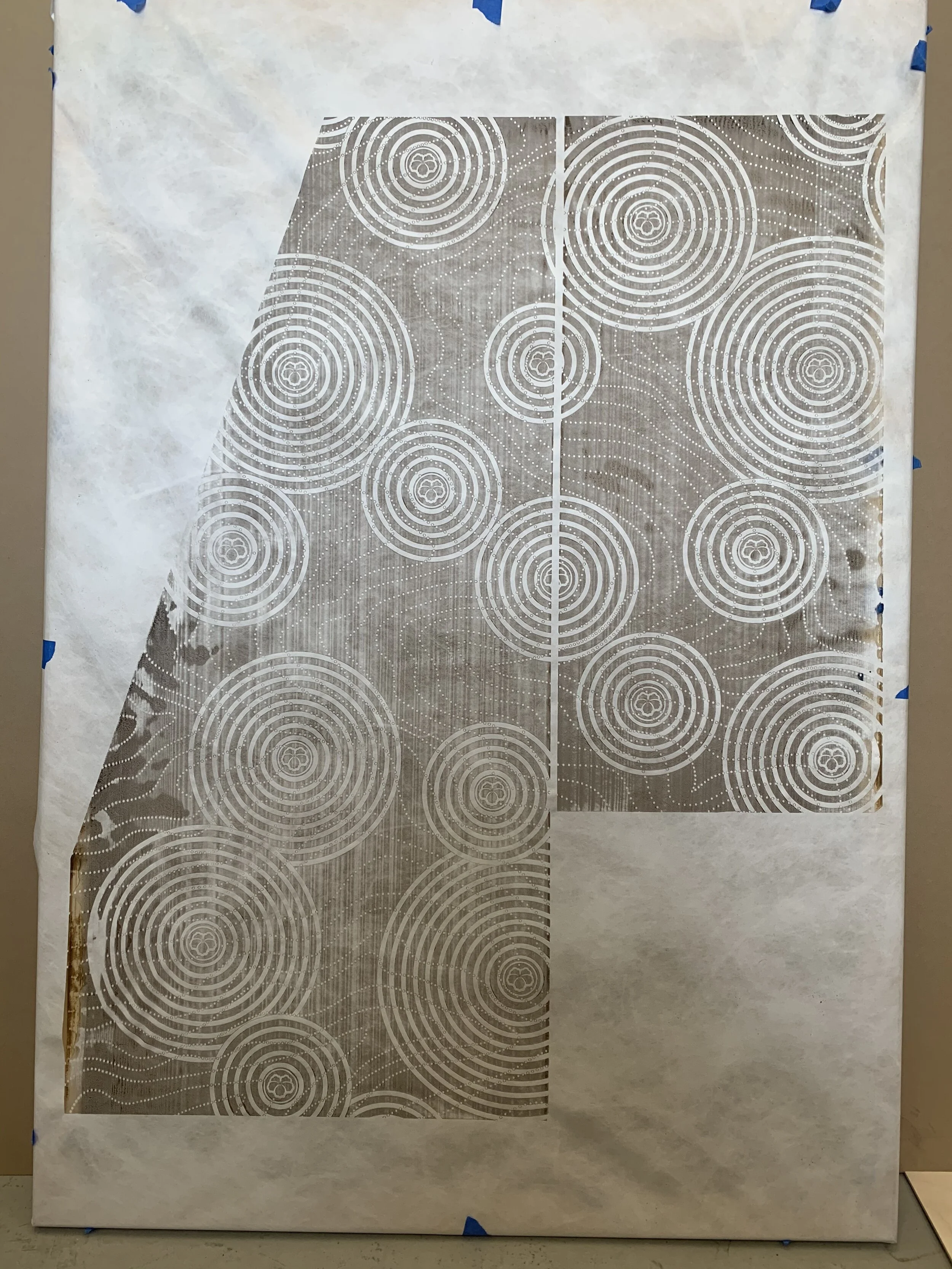

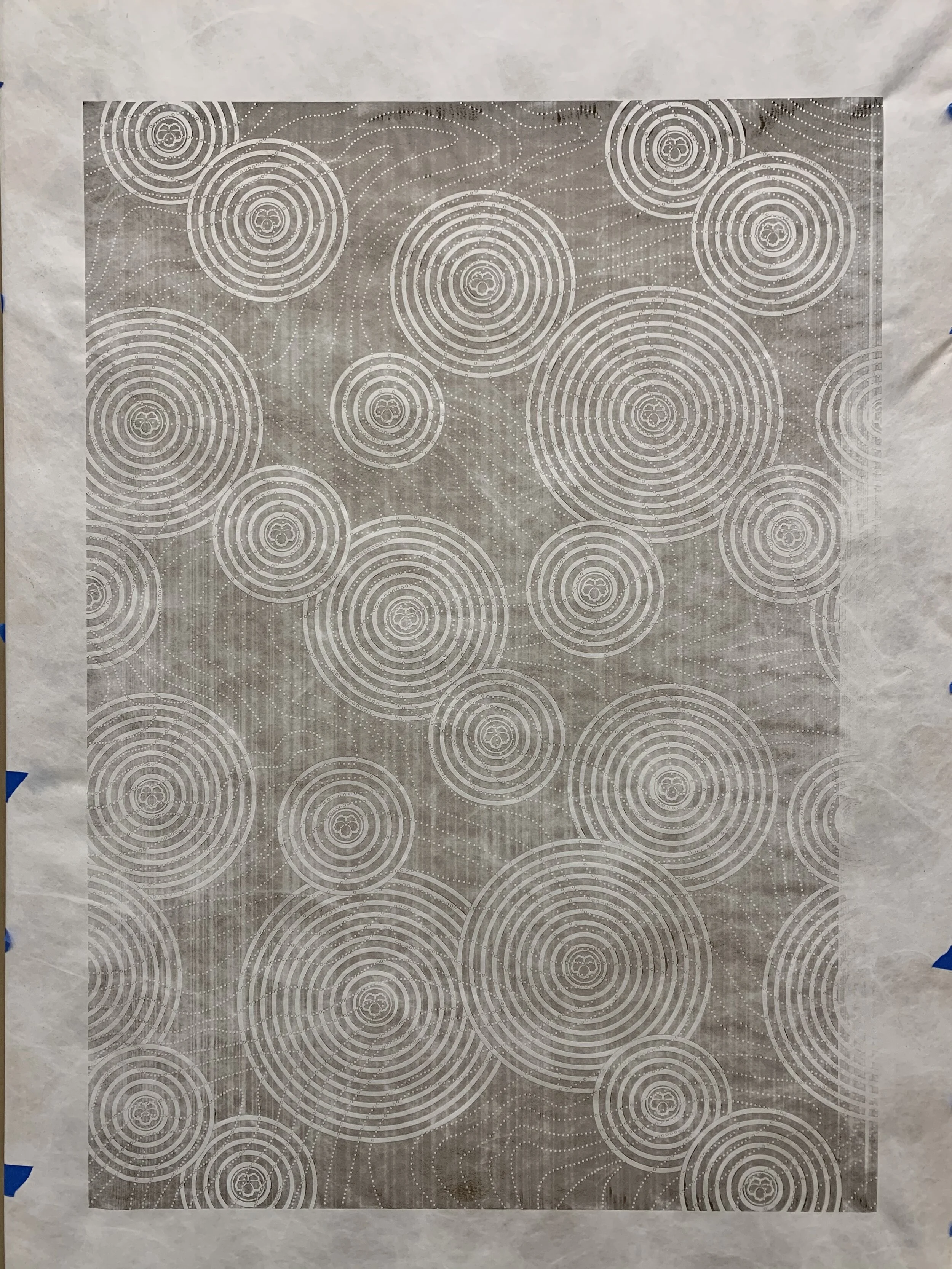

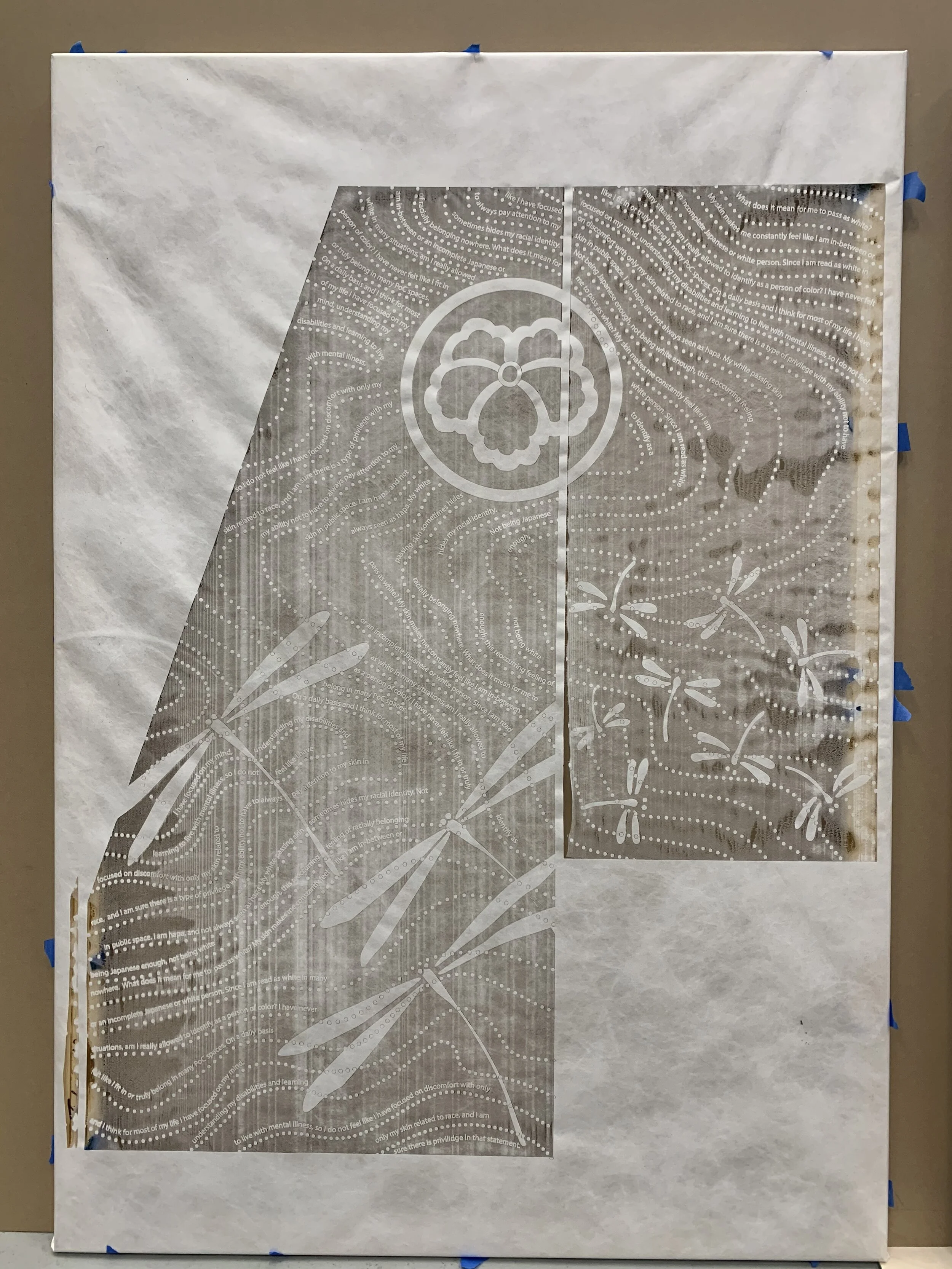

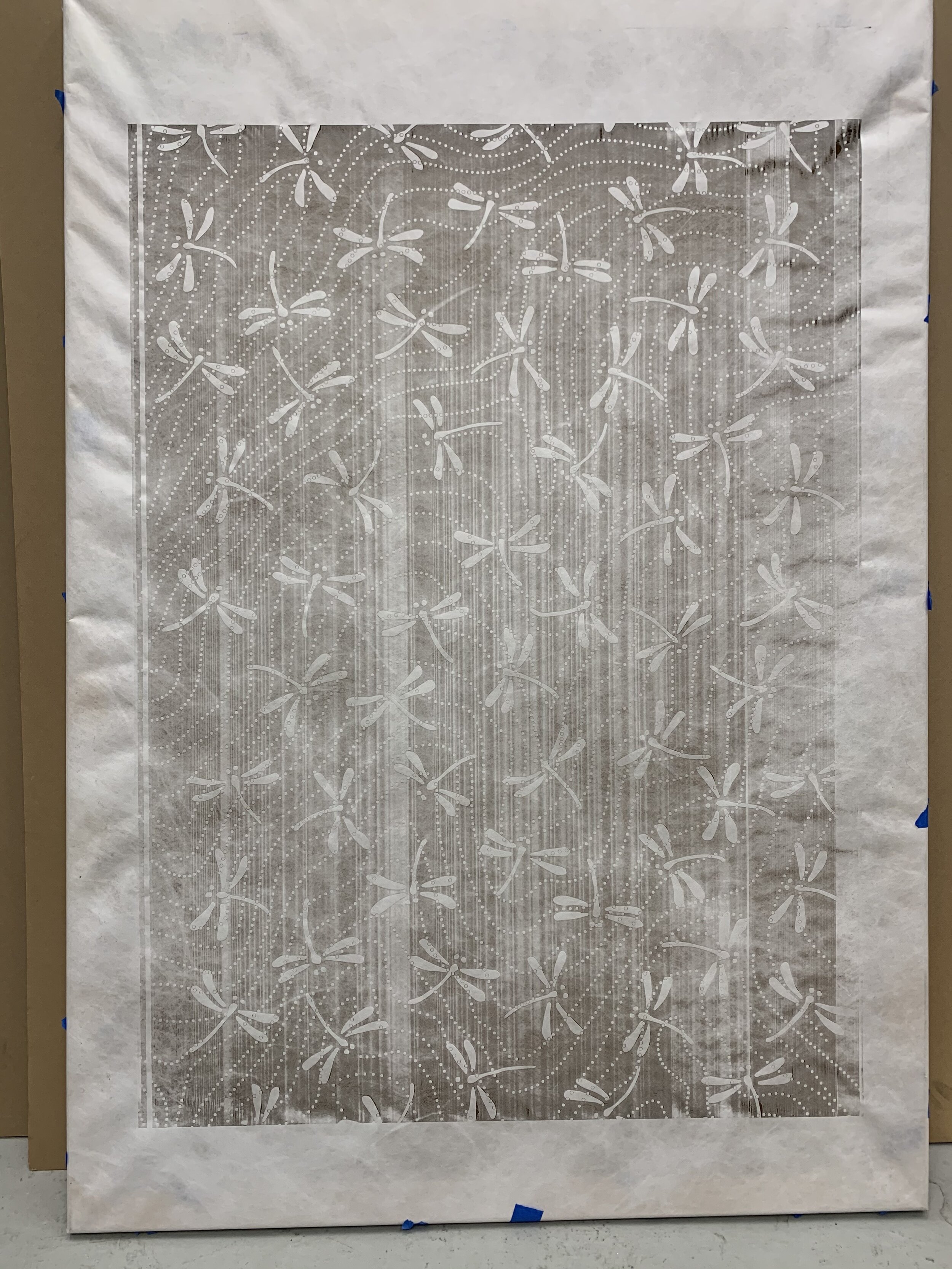

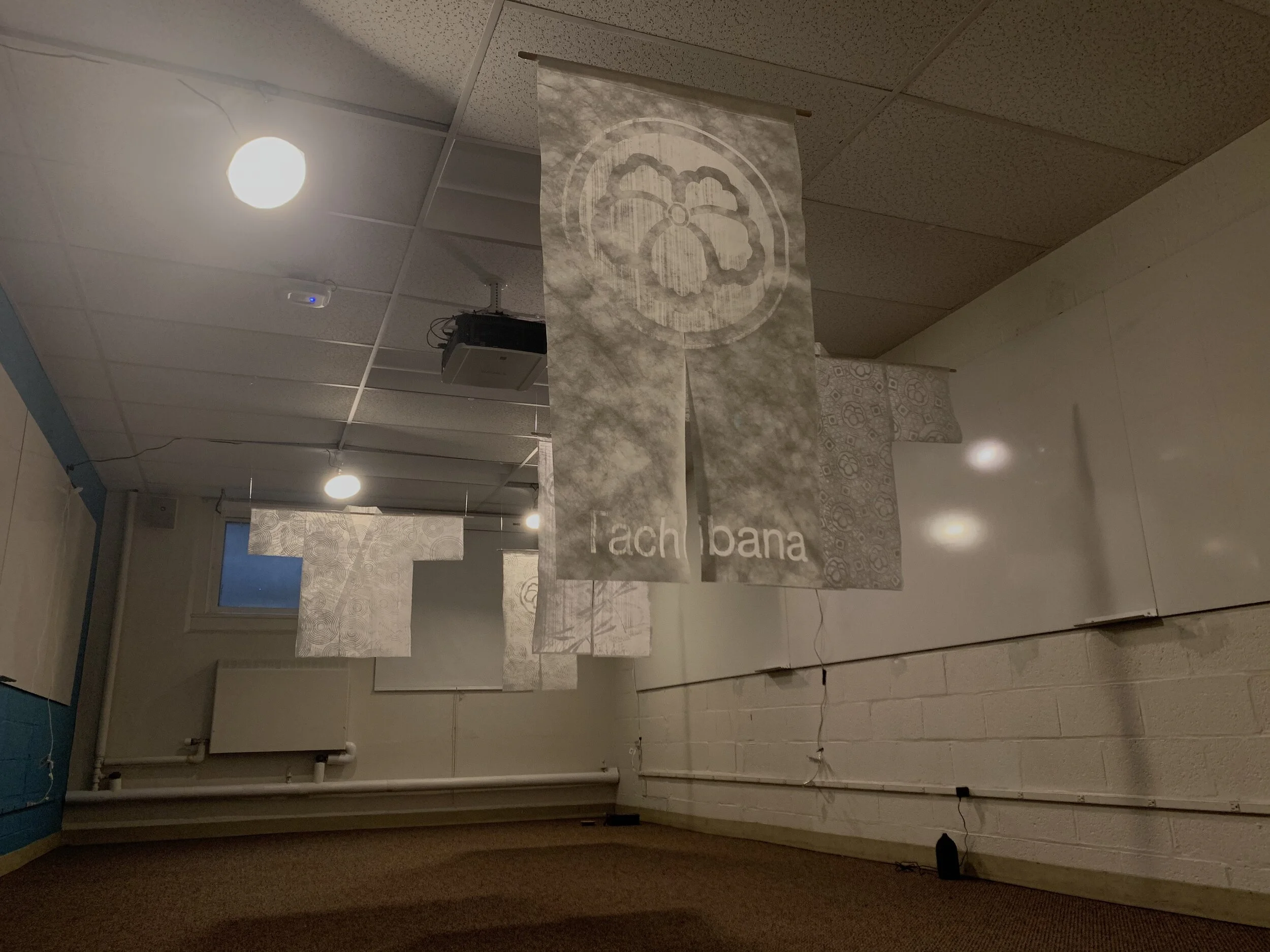

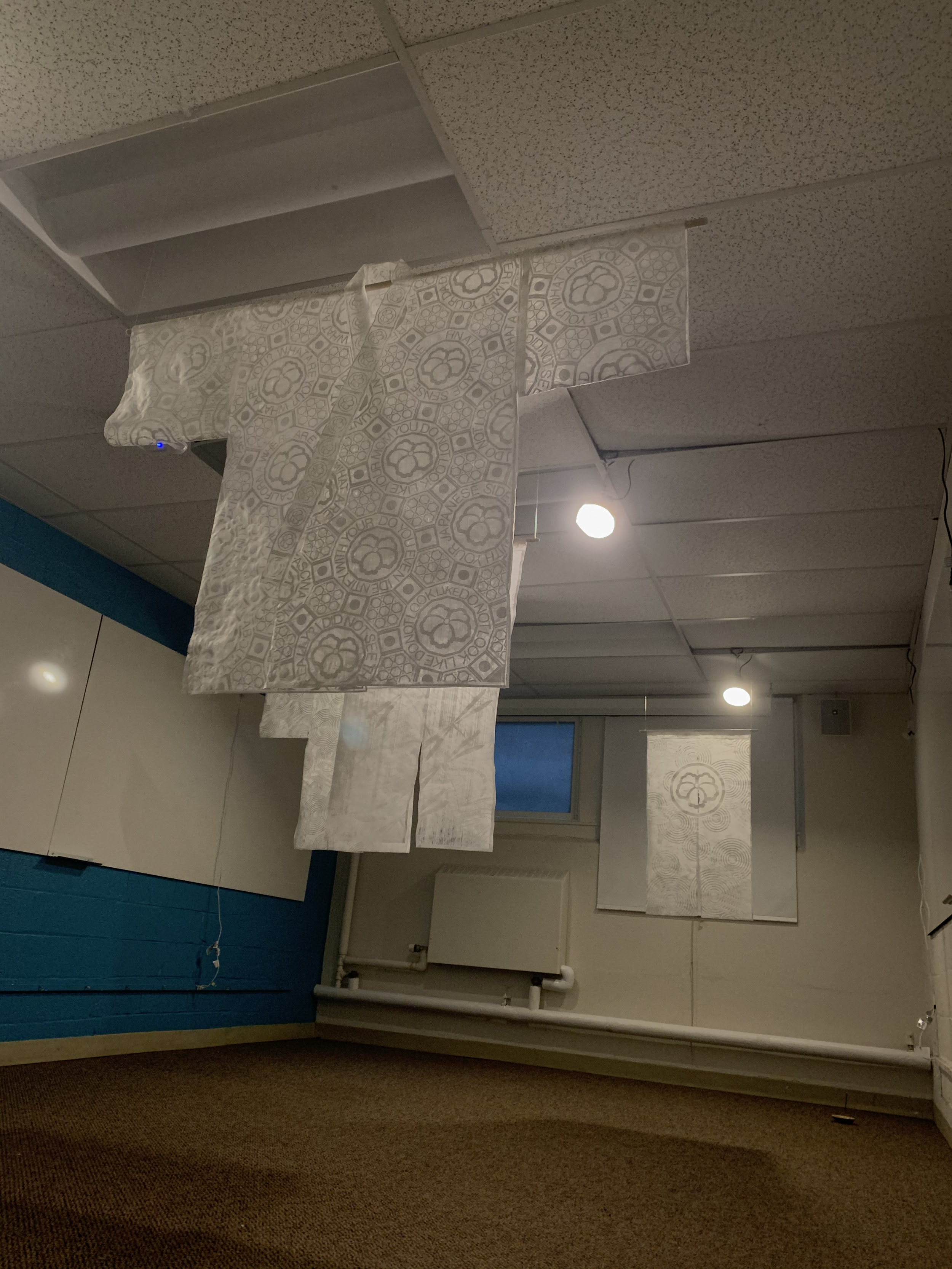

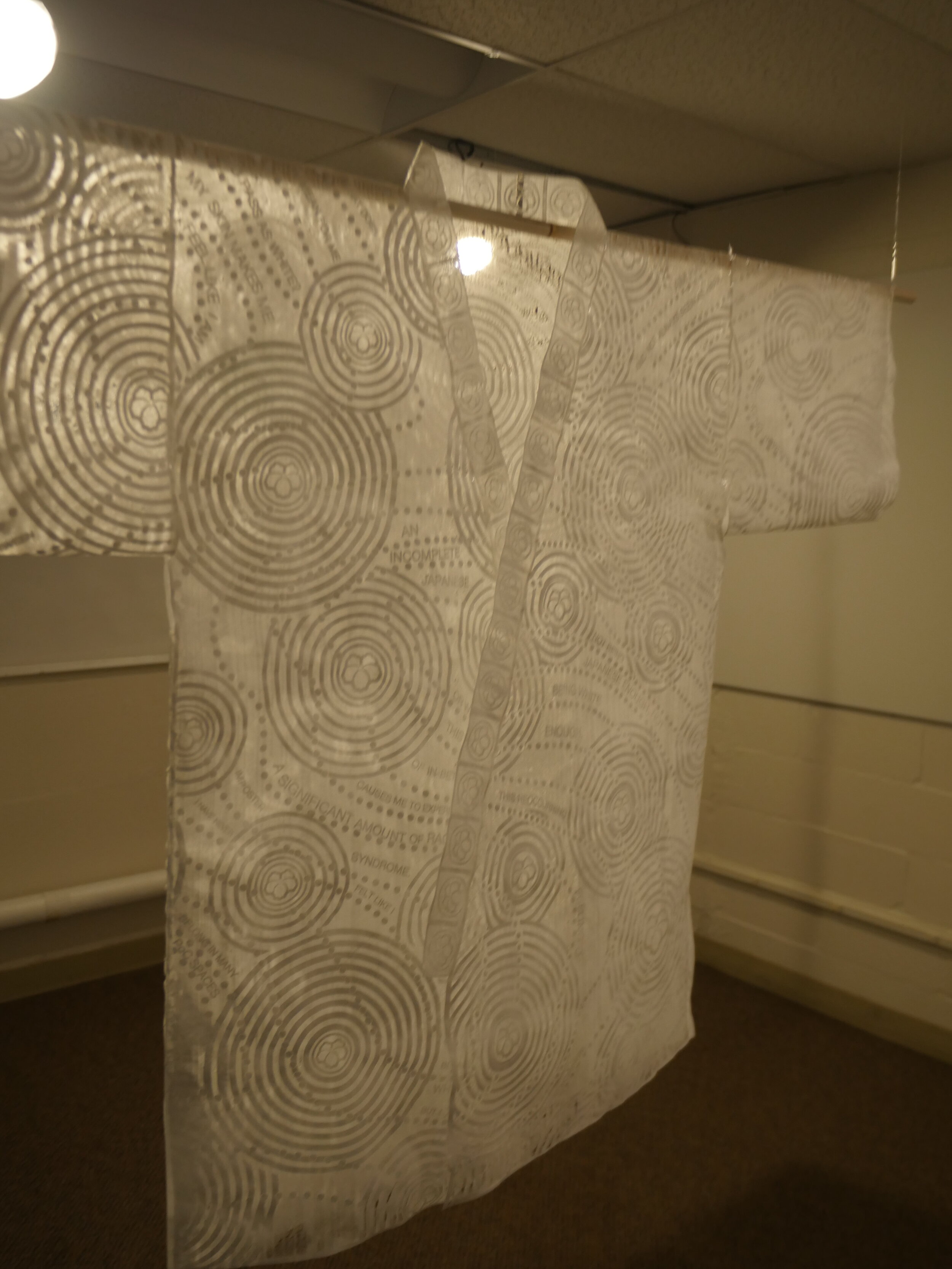

Skin Memory, 2020

tyvek, wood, oil diffusers, incense, sound

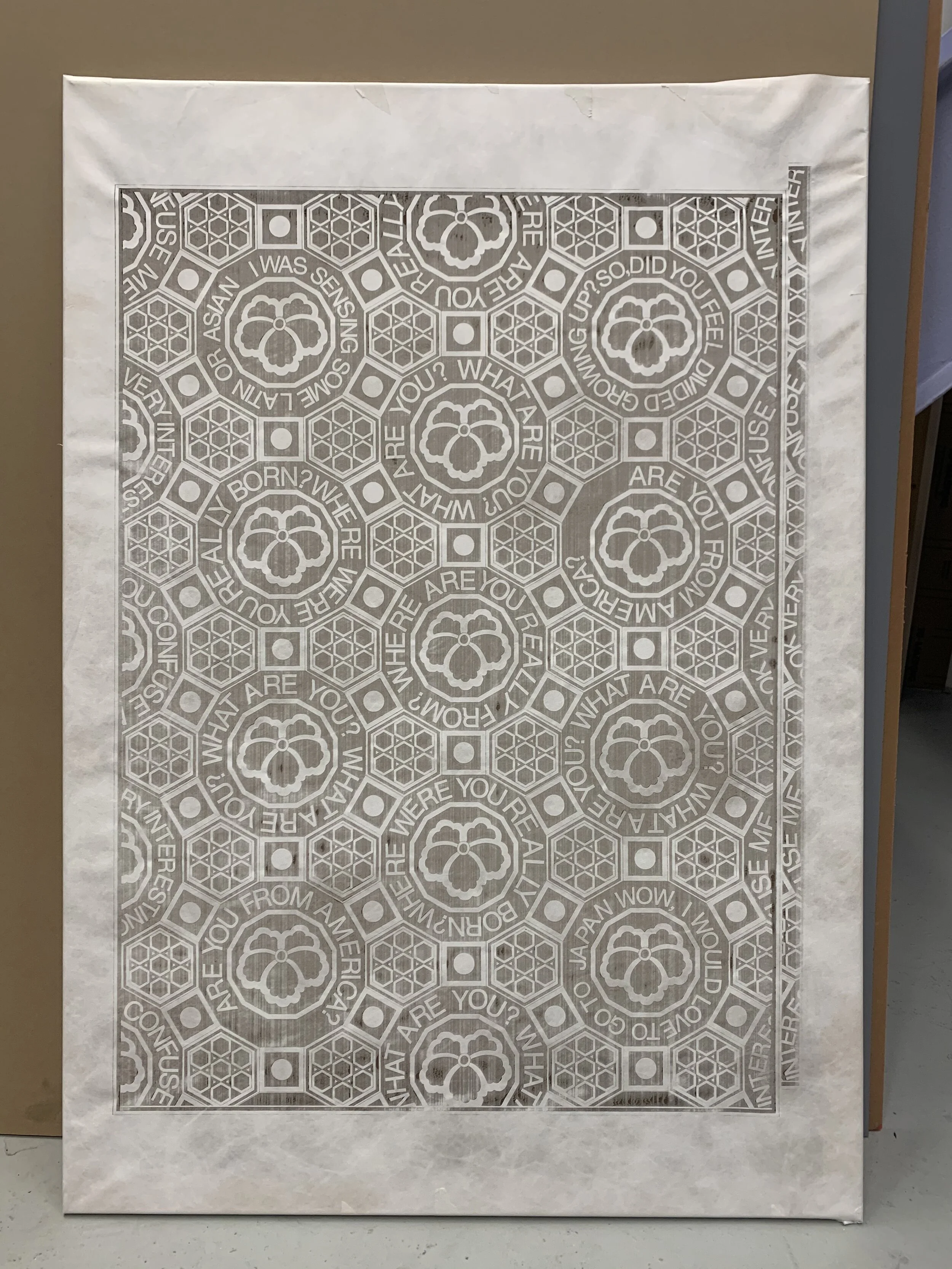

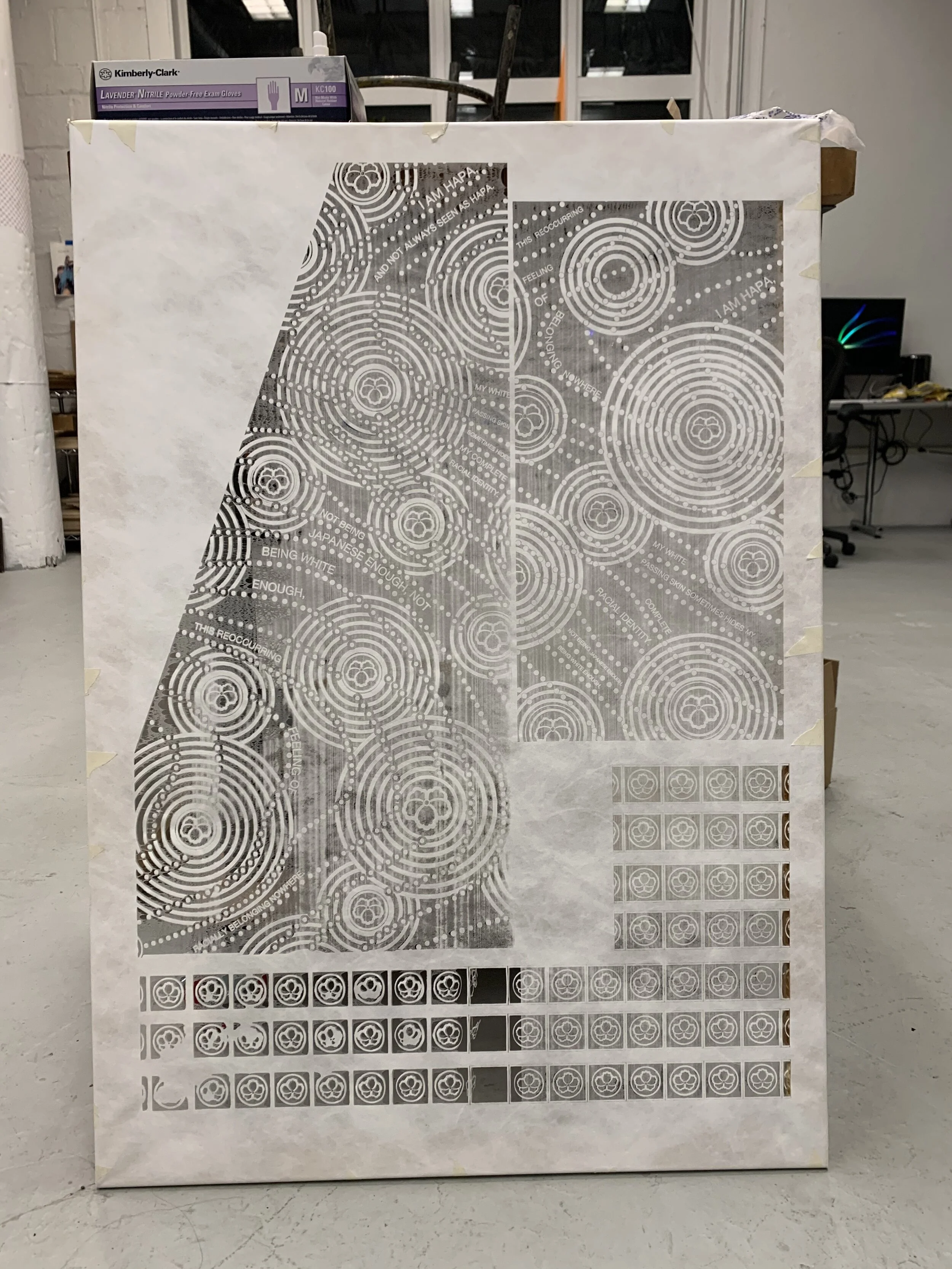

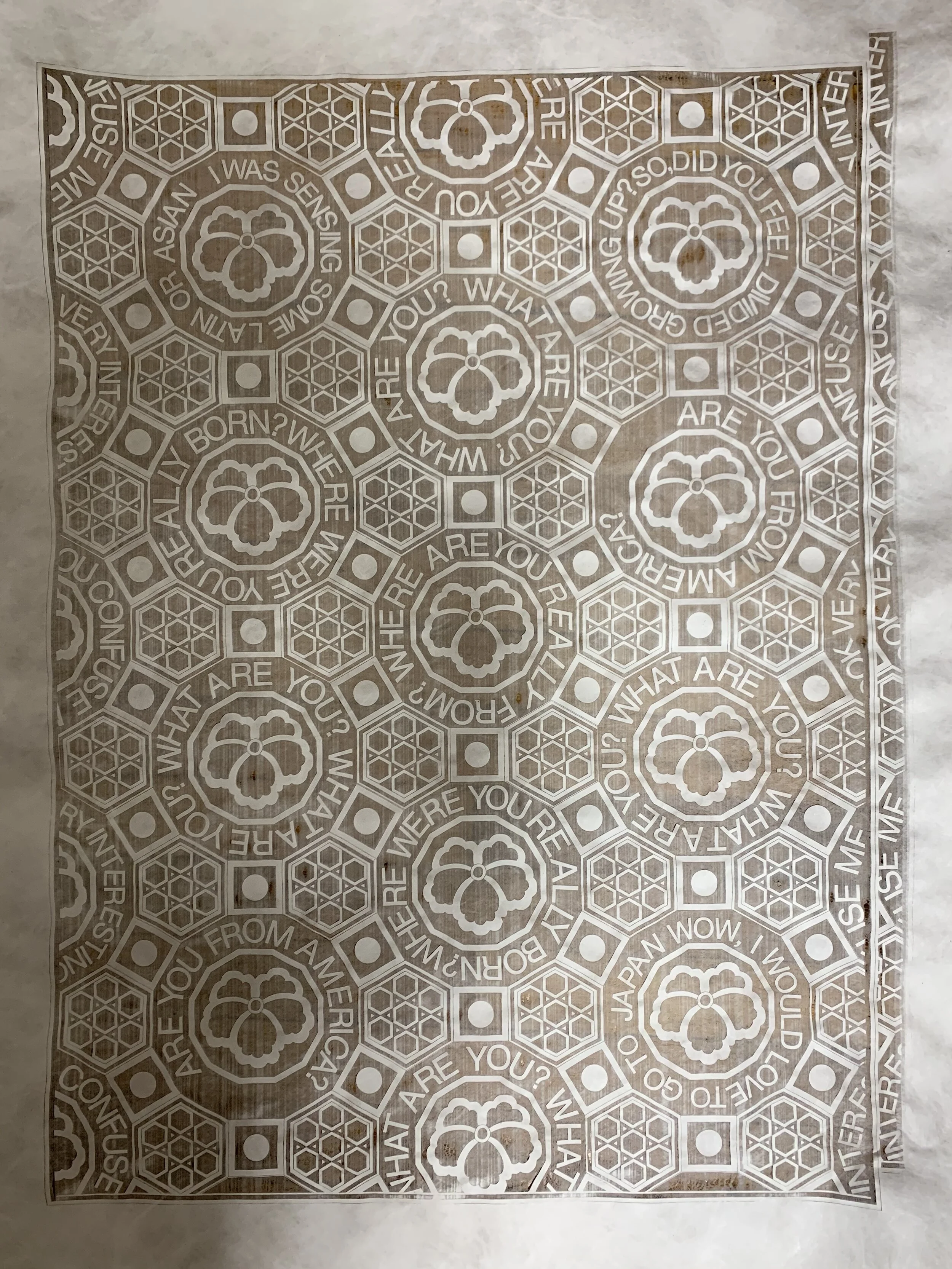

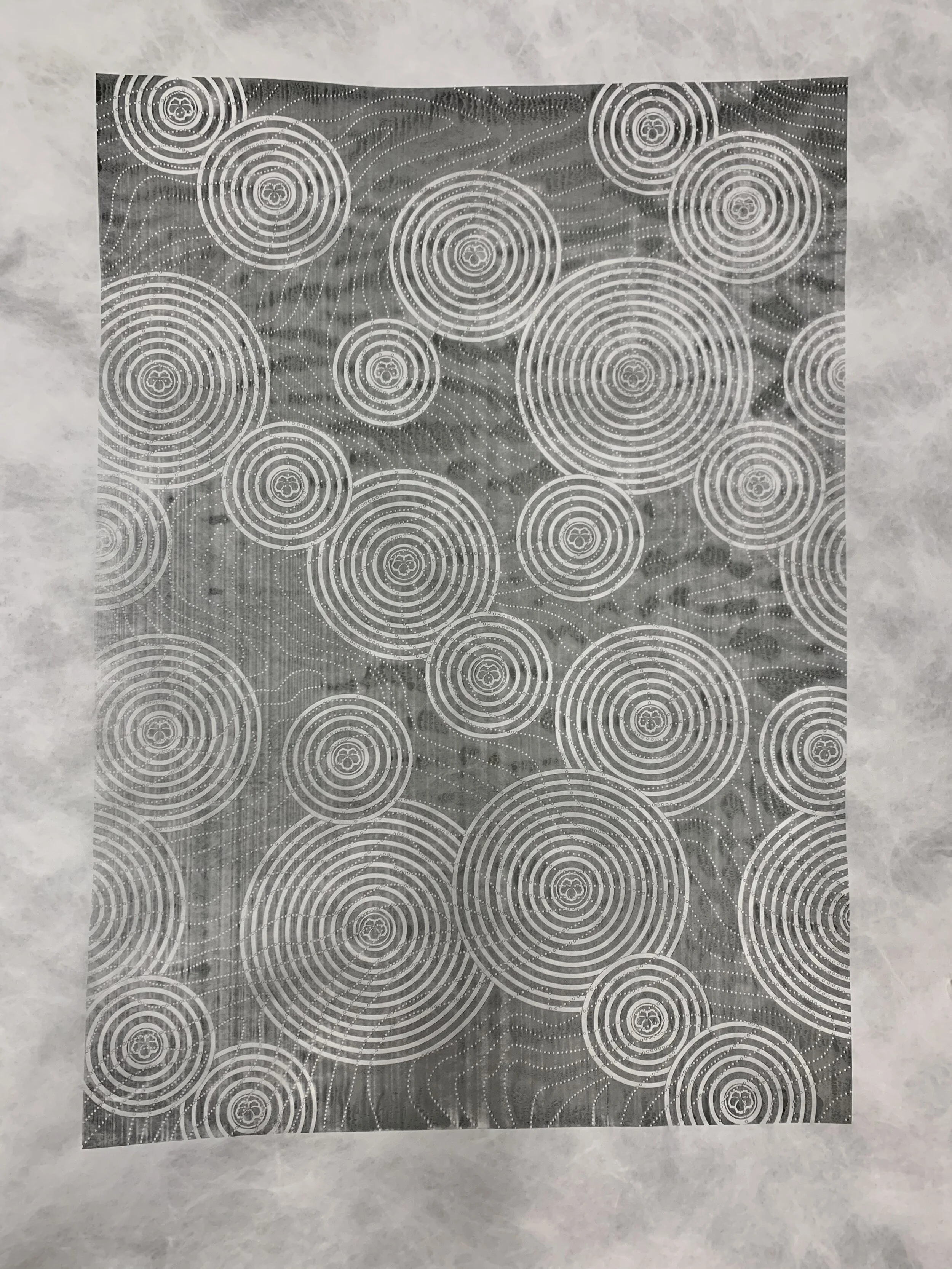

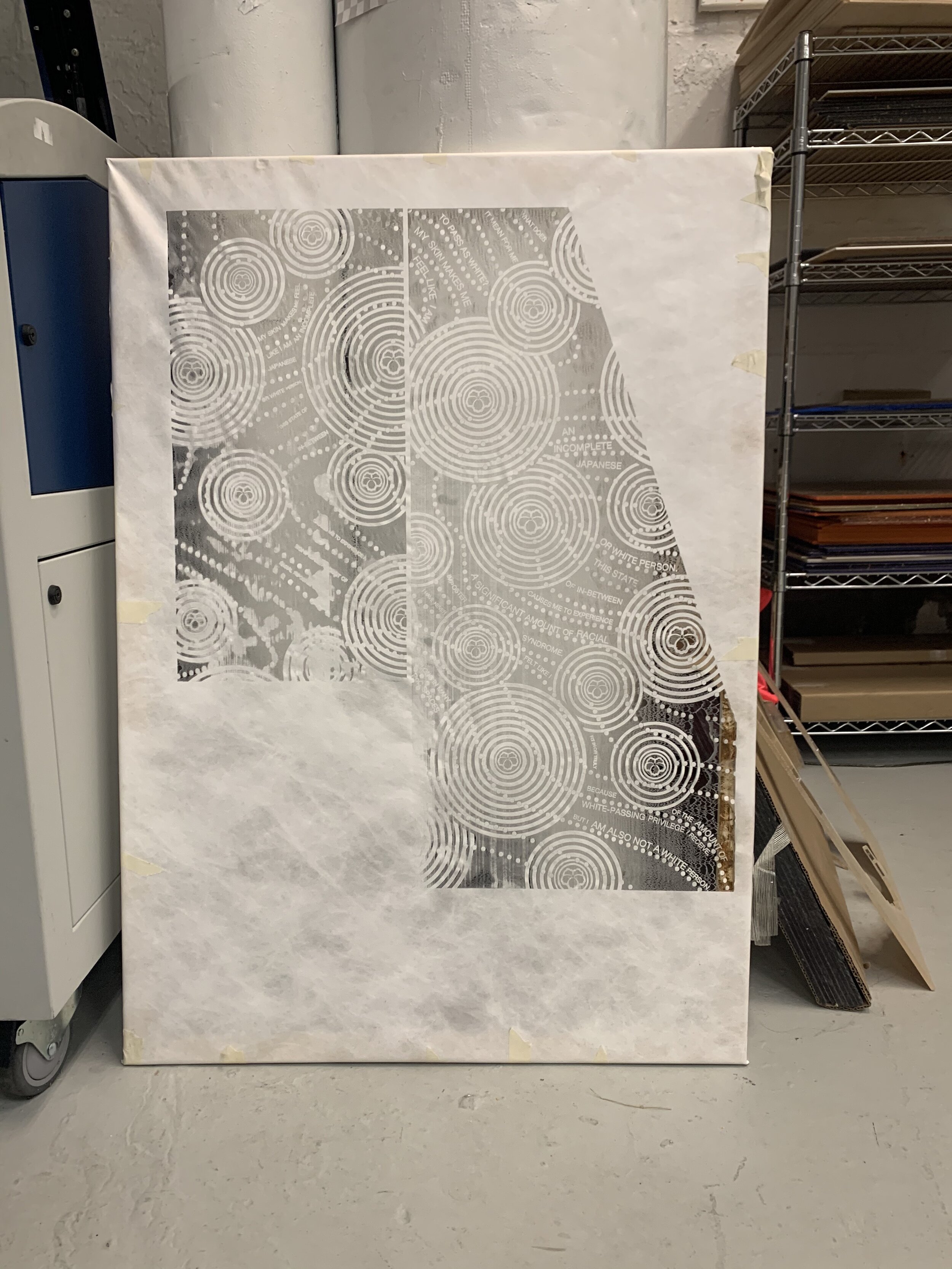

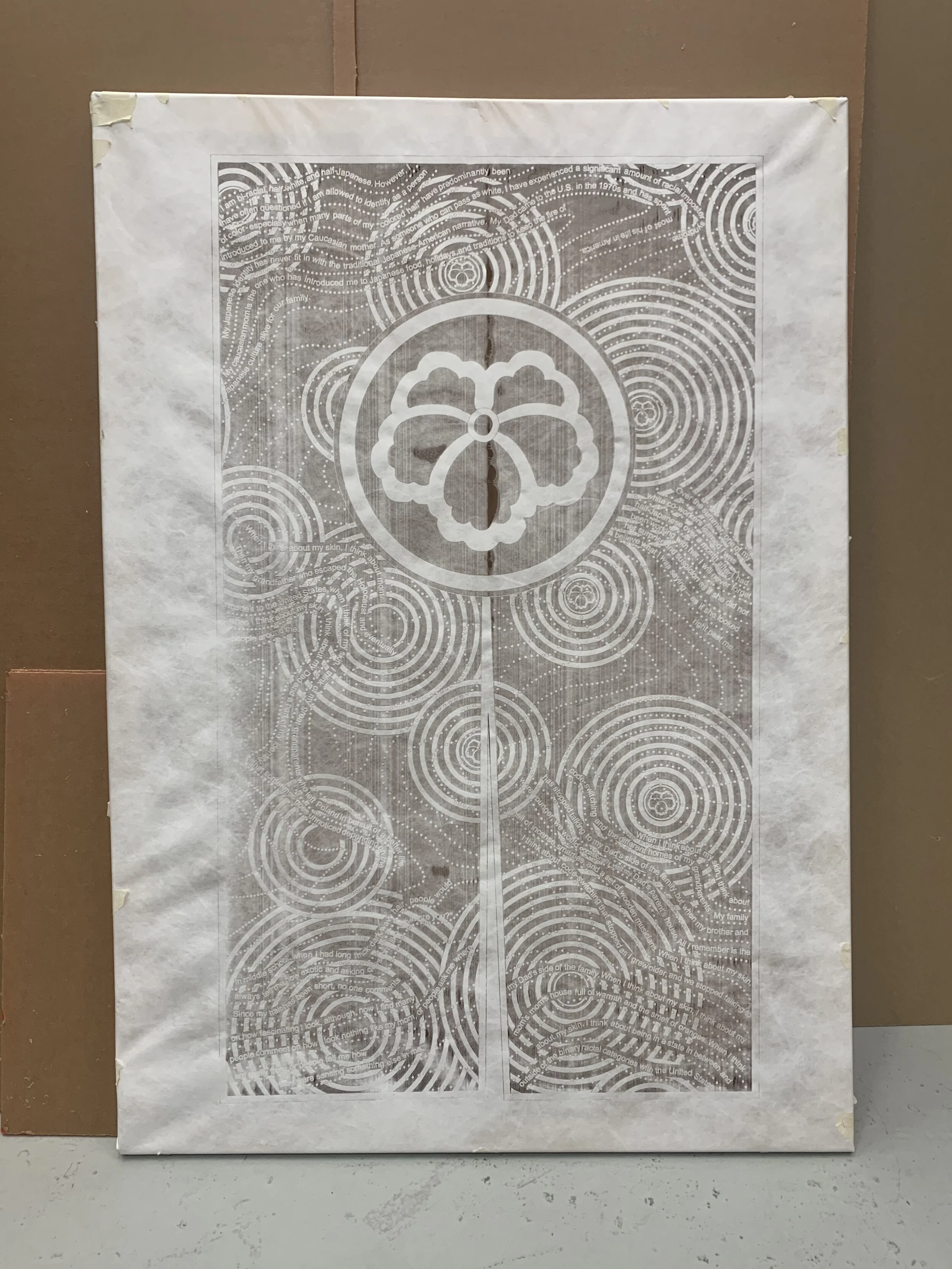

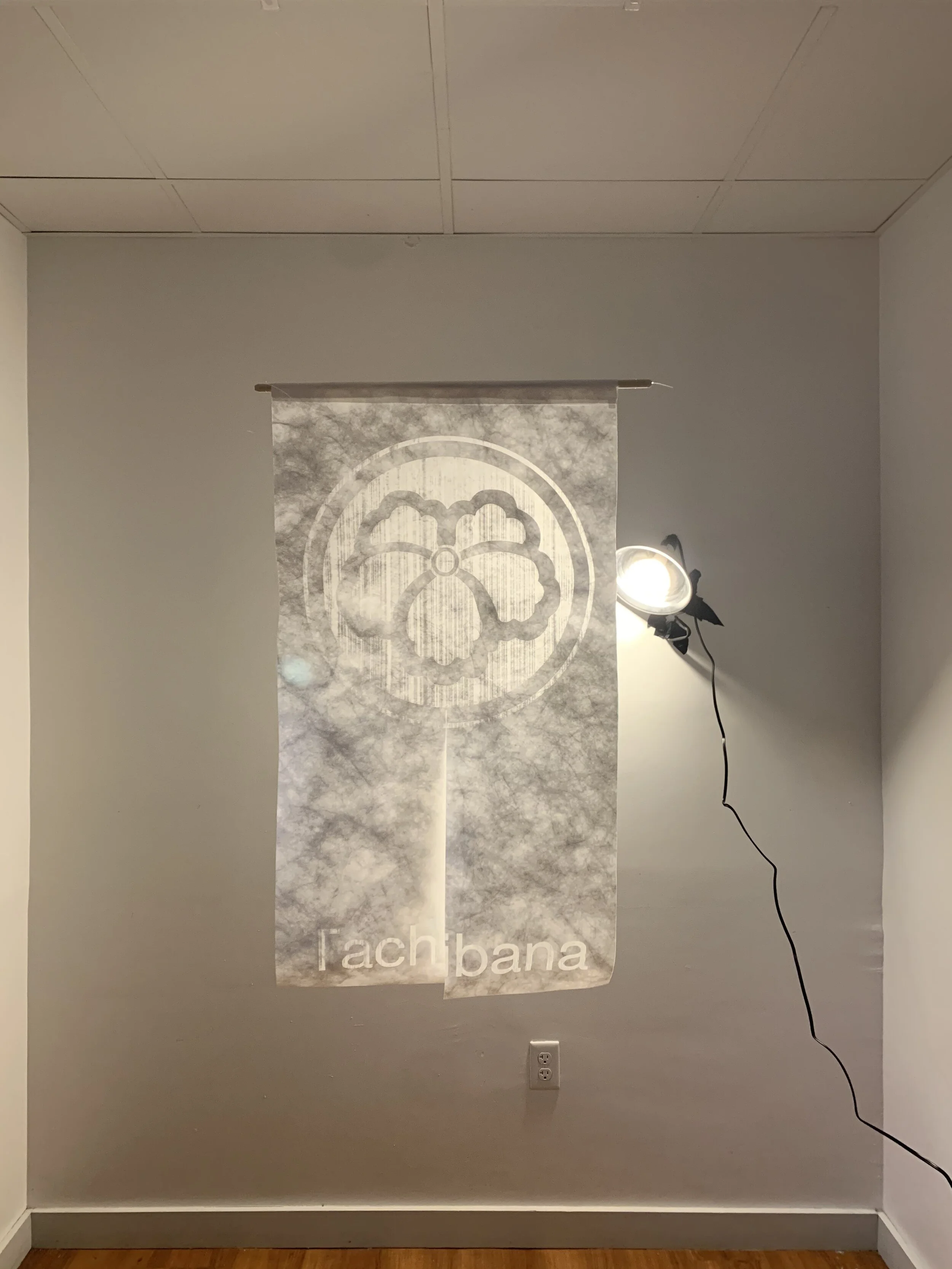

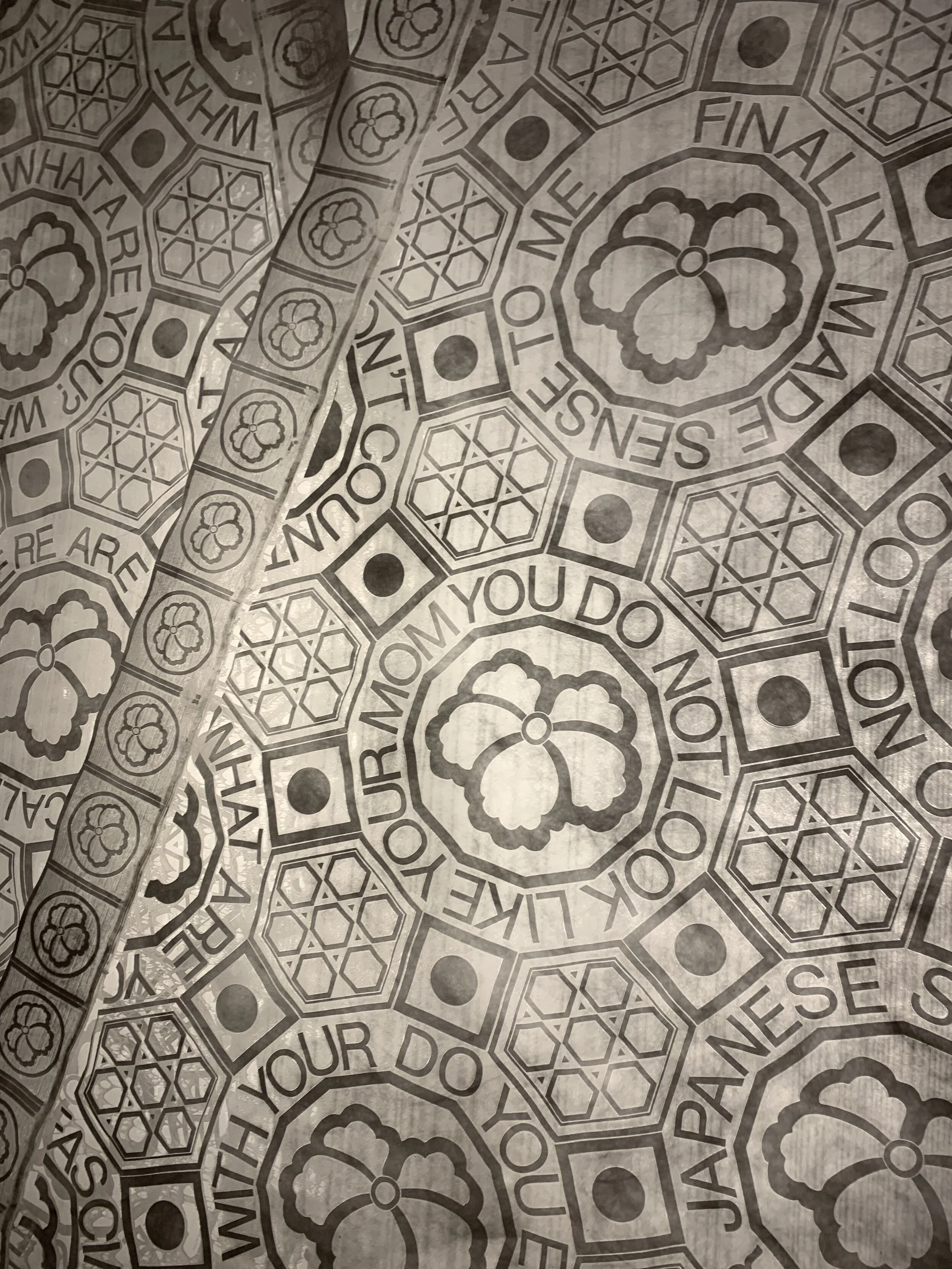

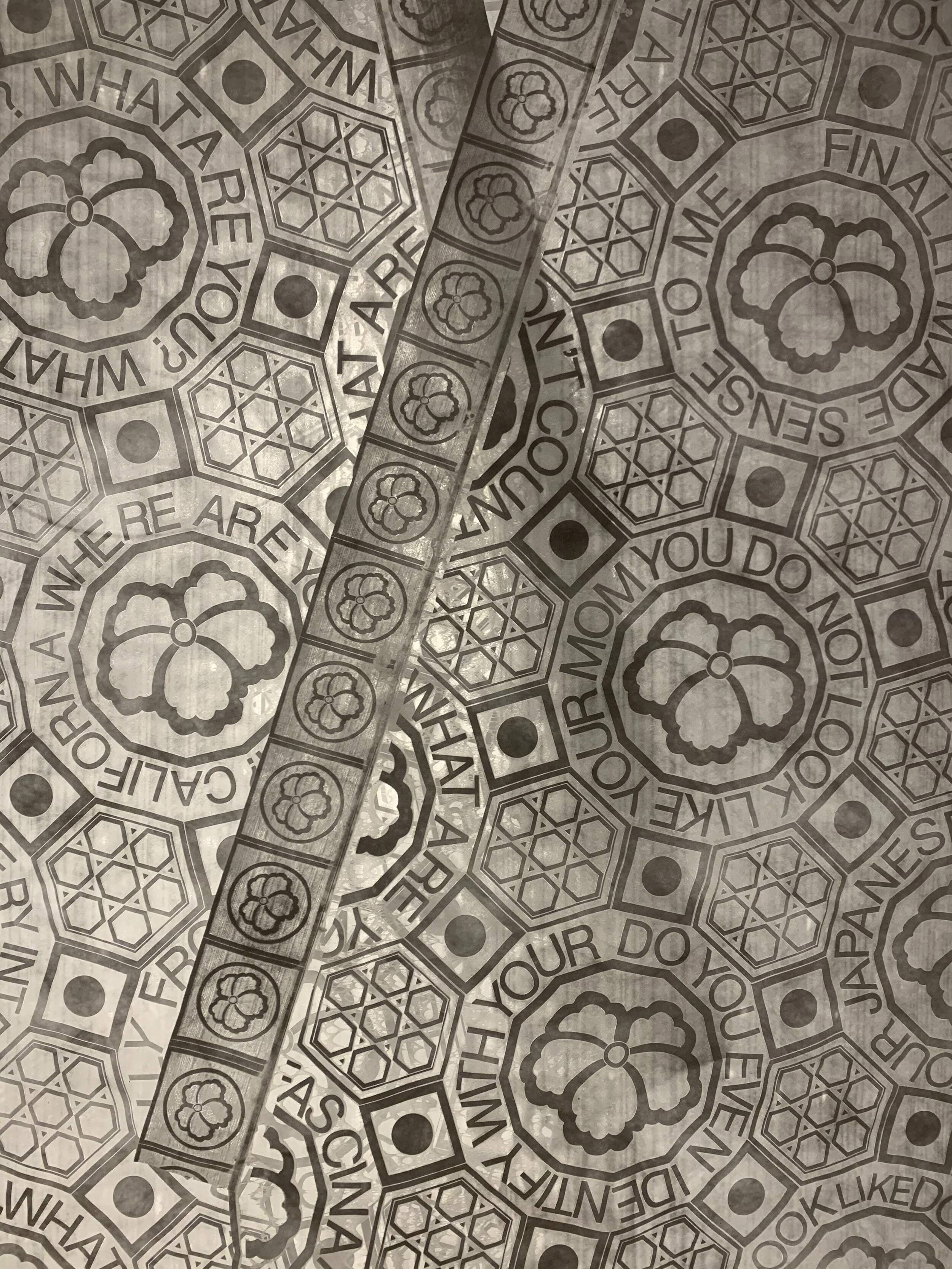

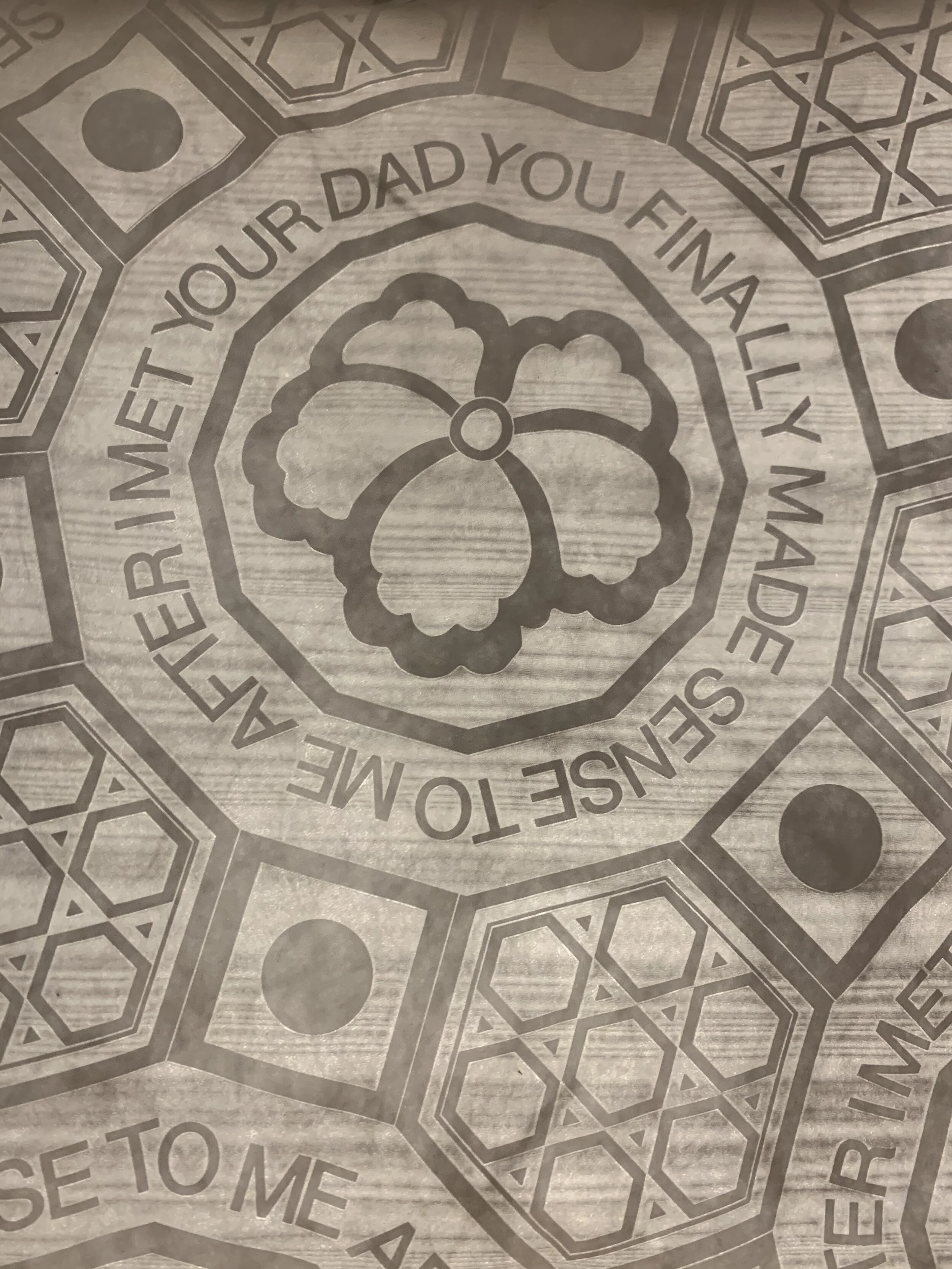

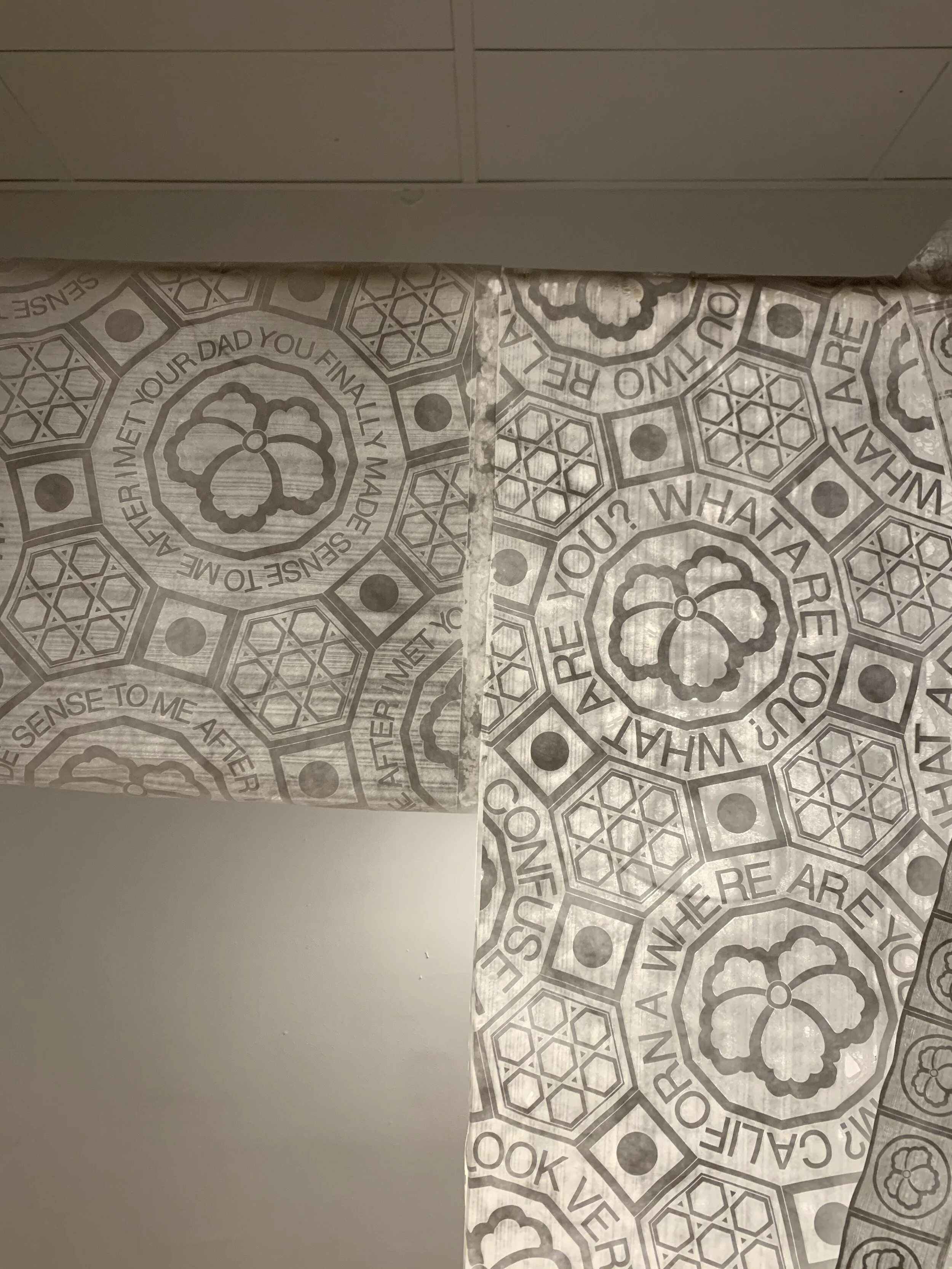

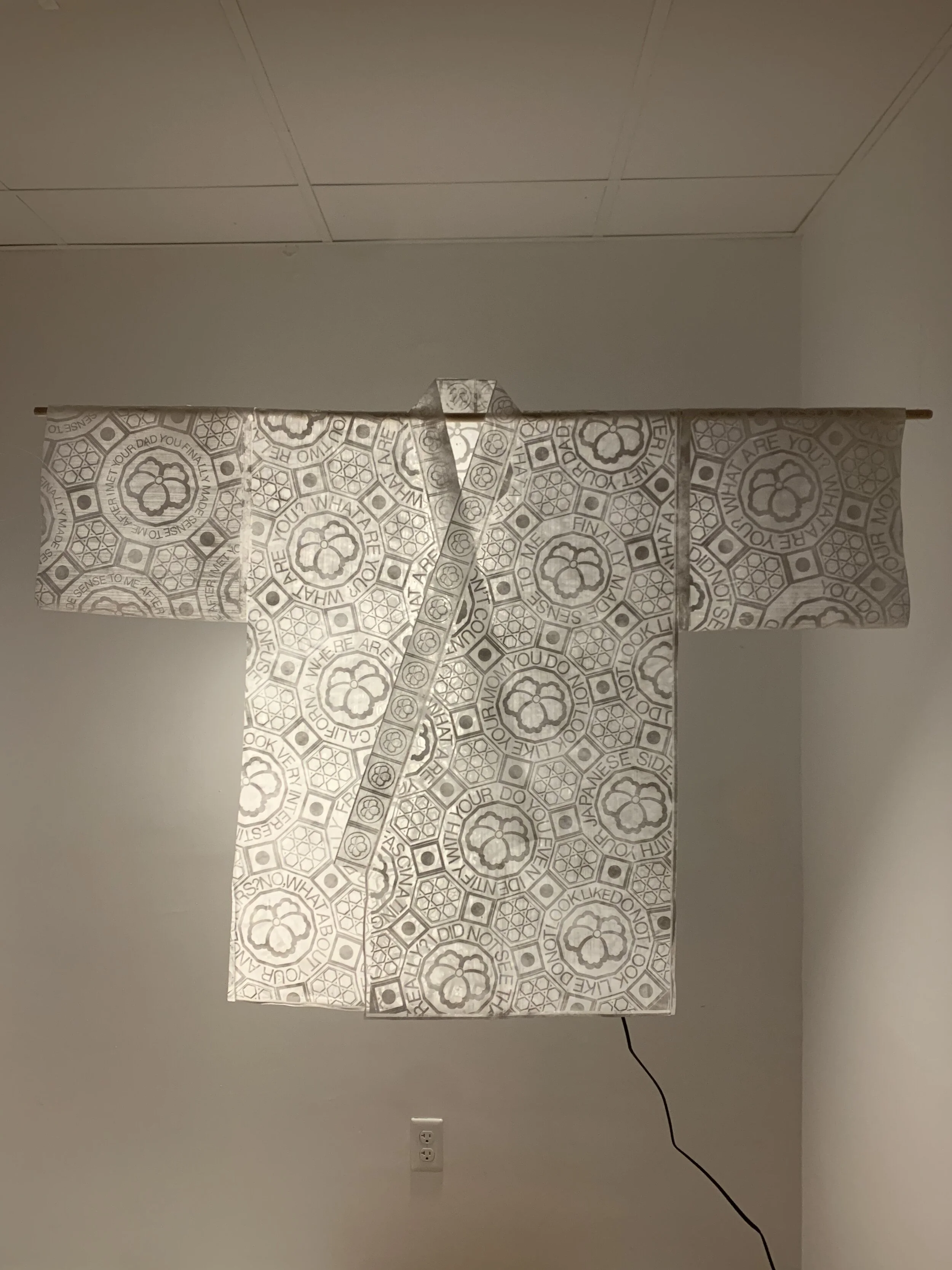

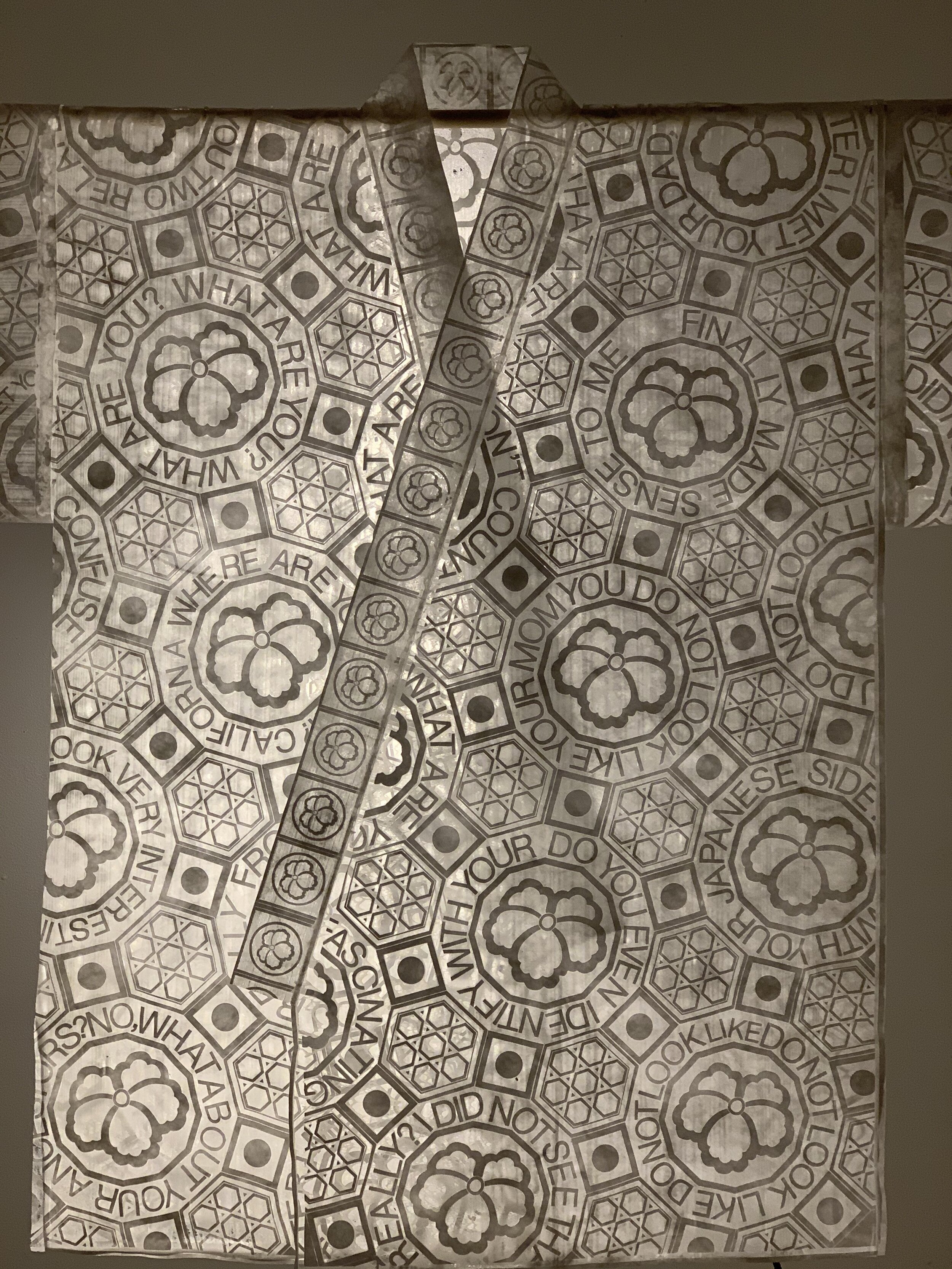

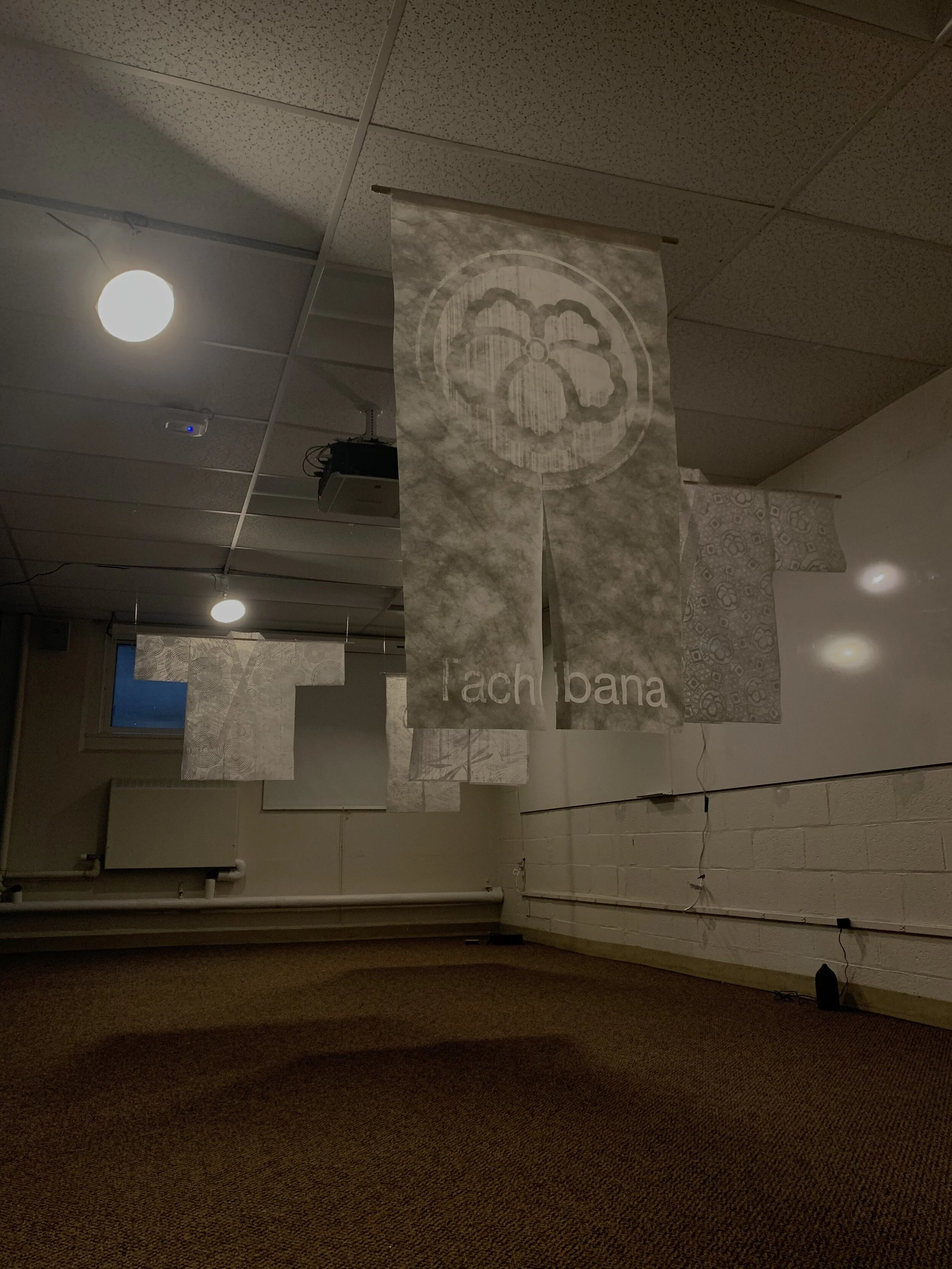

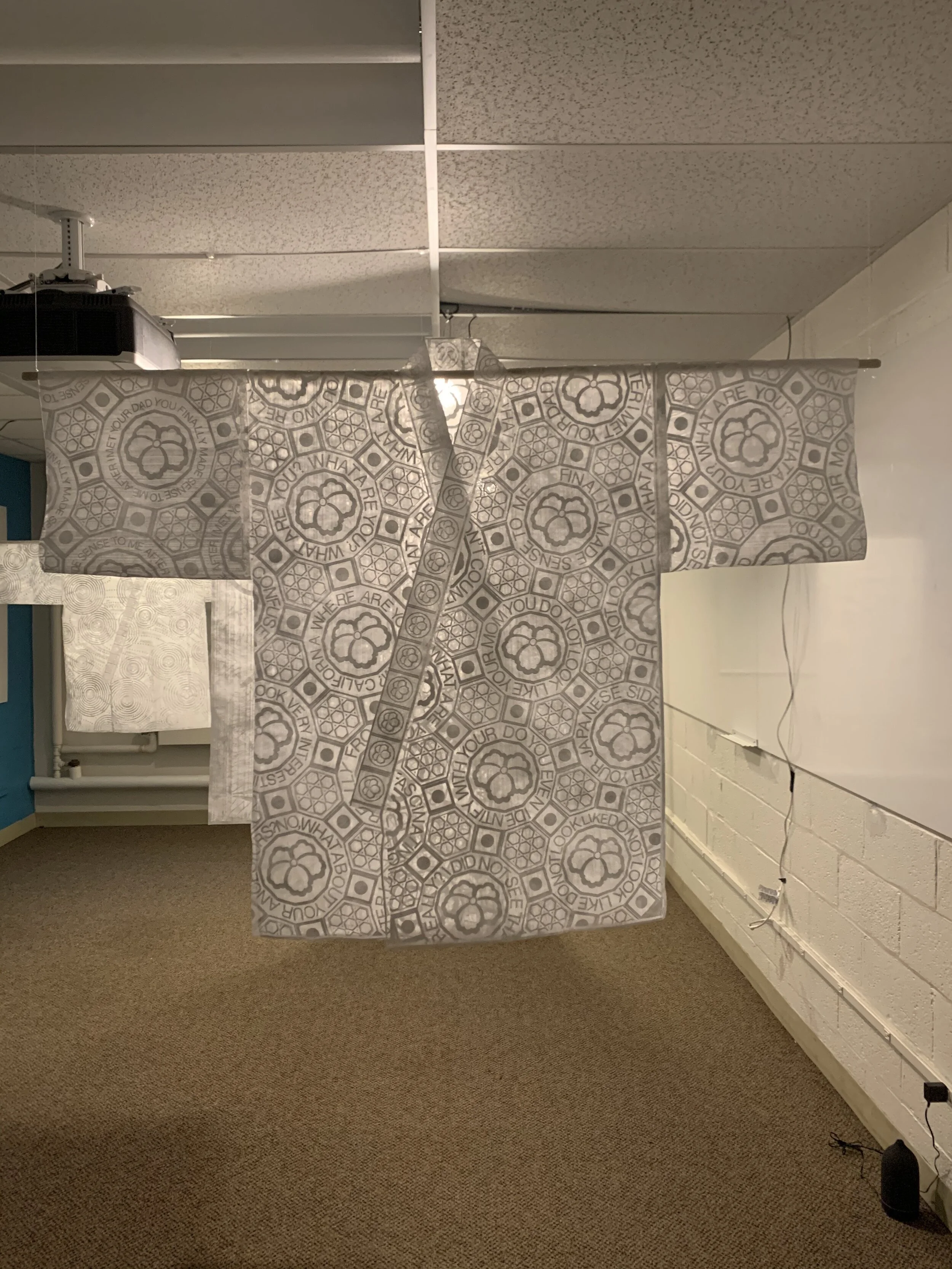

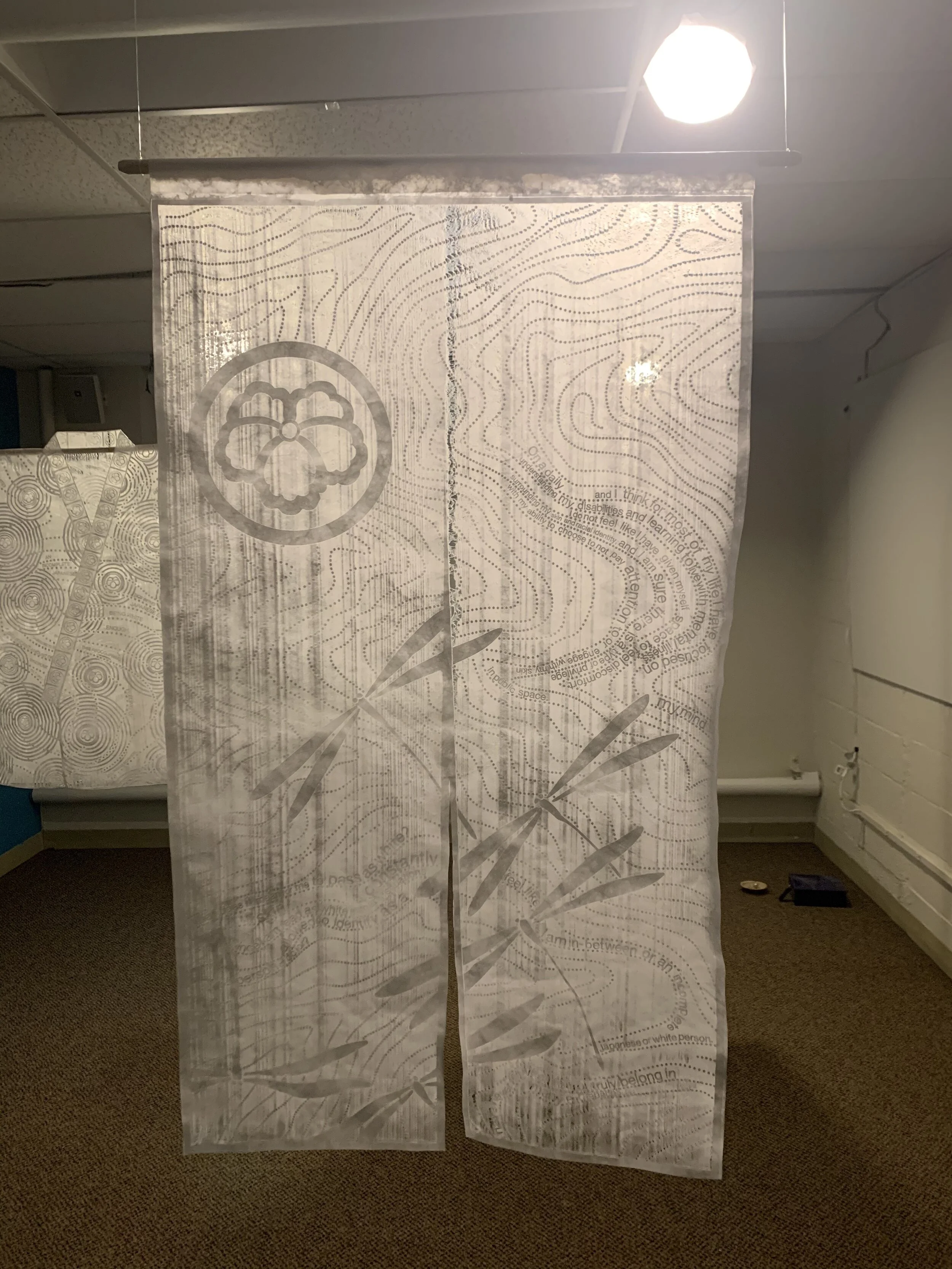

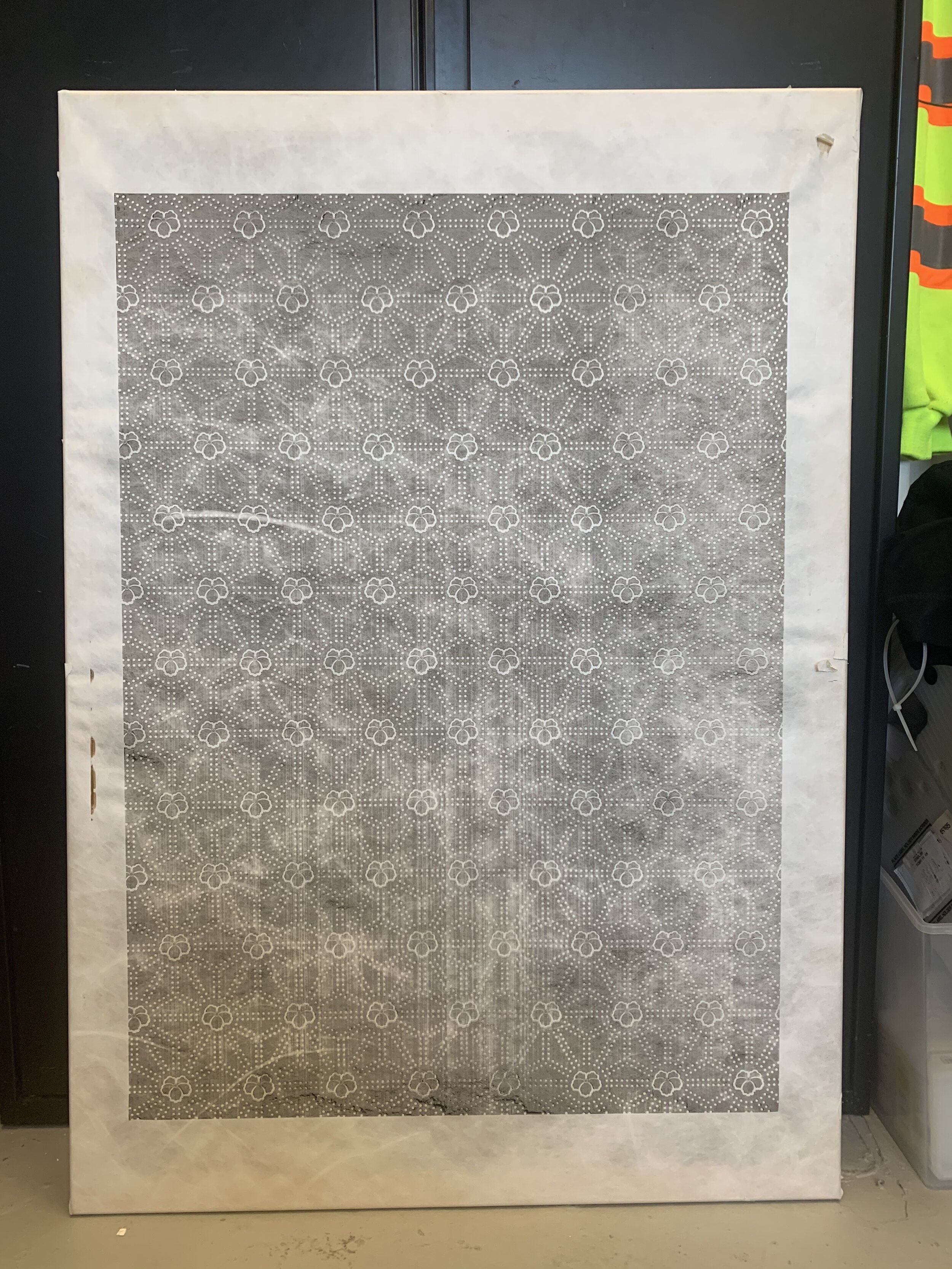

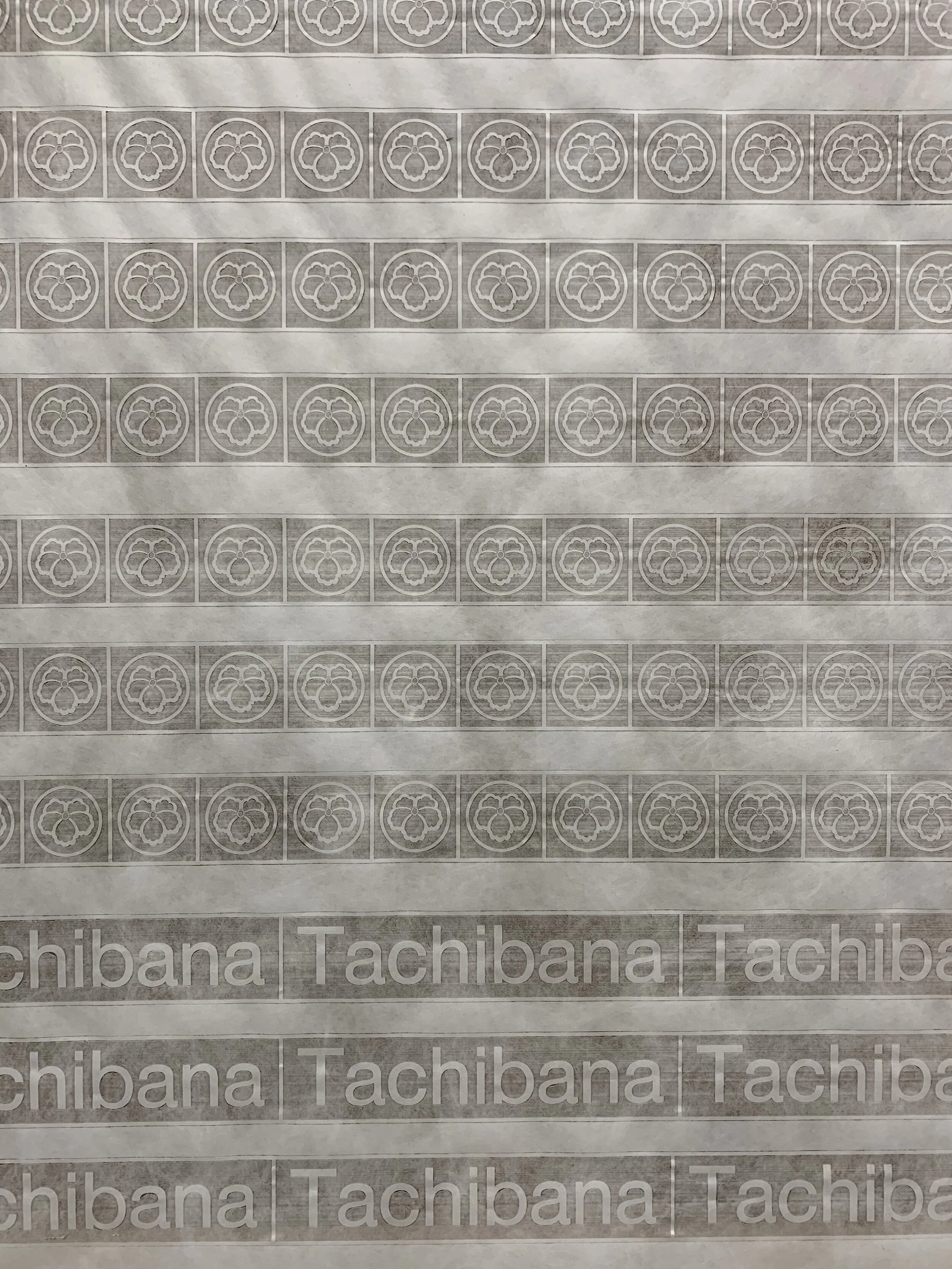

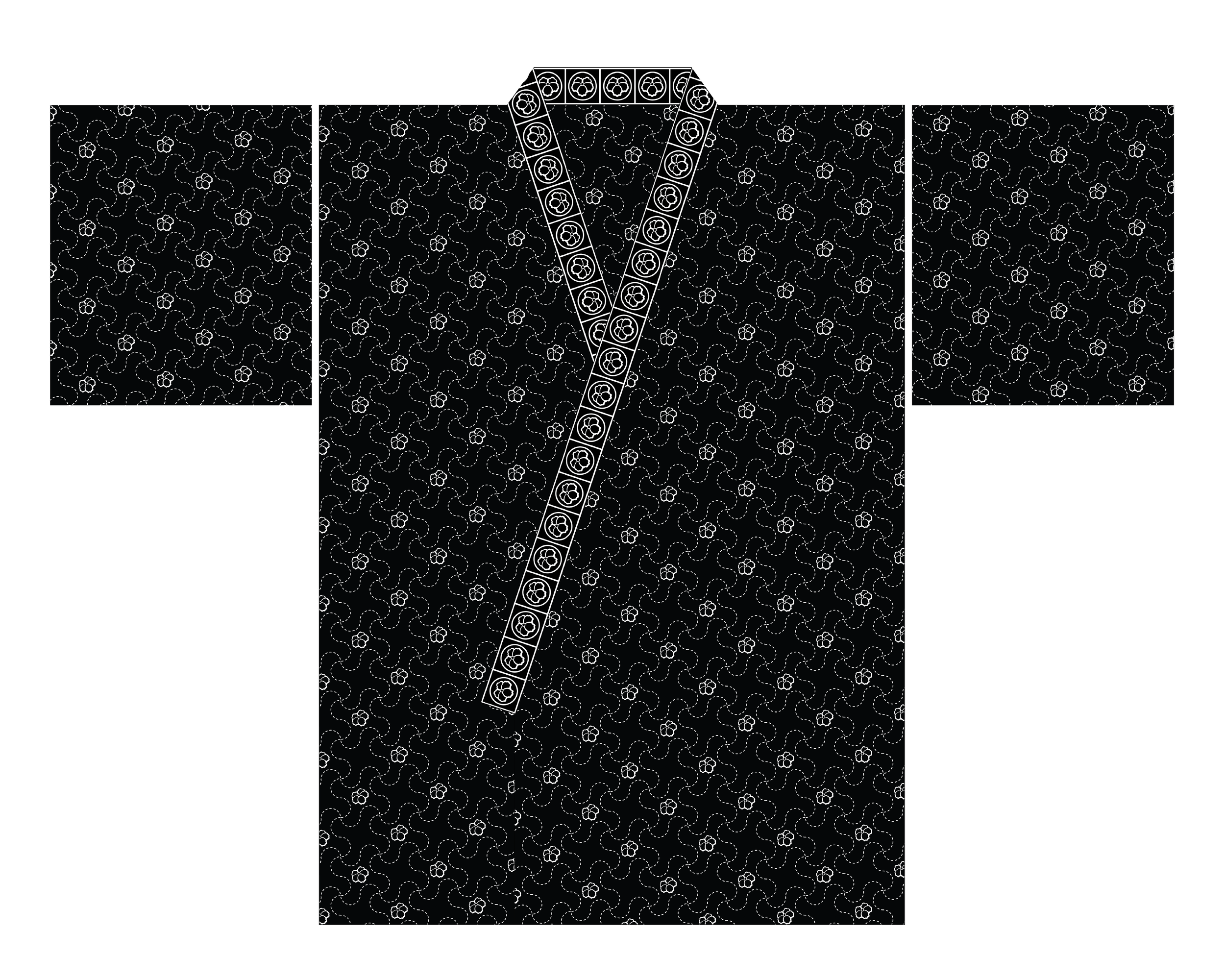

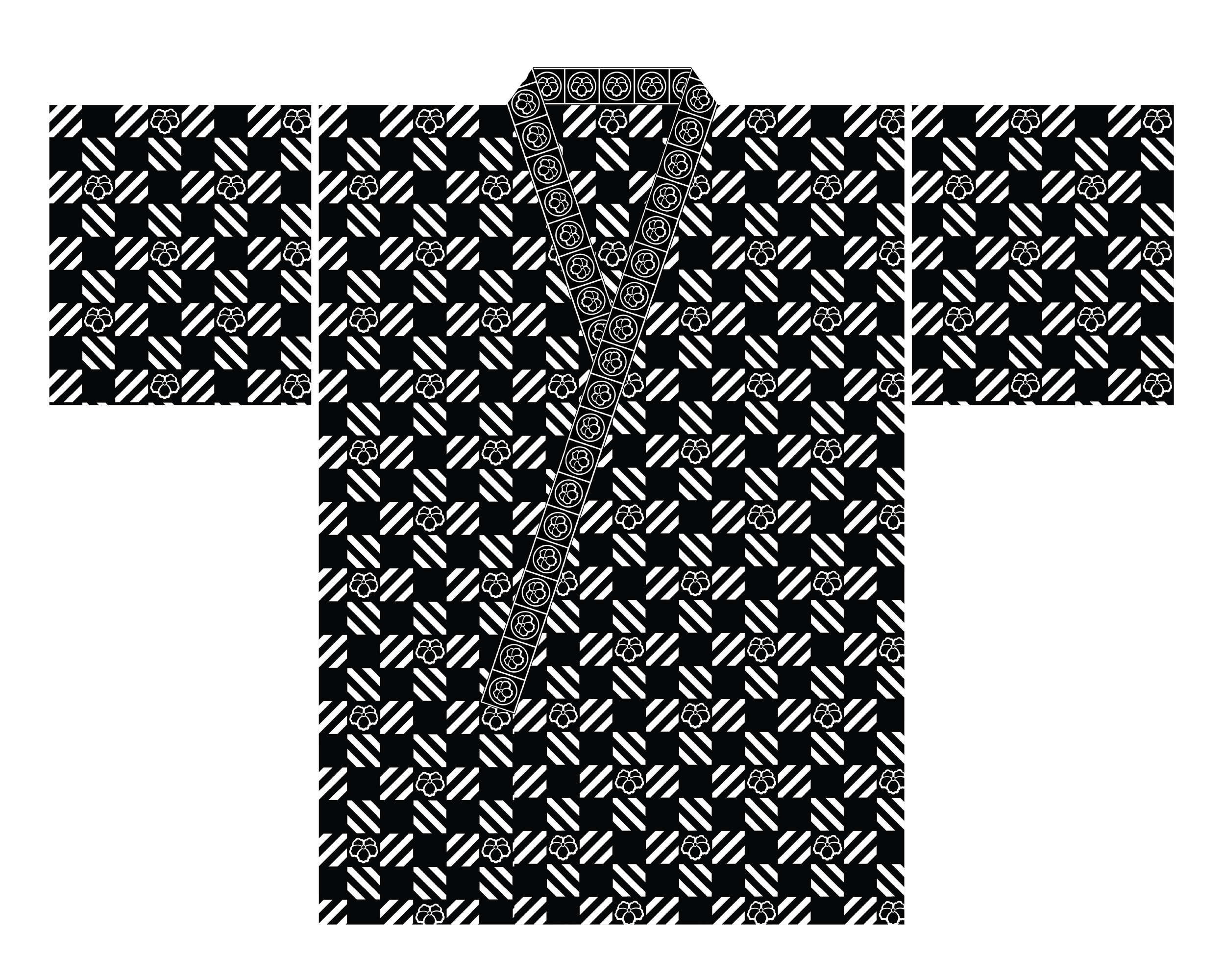

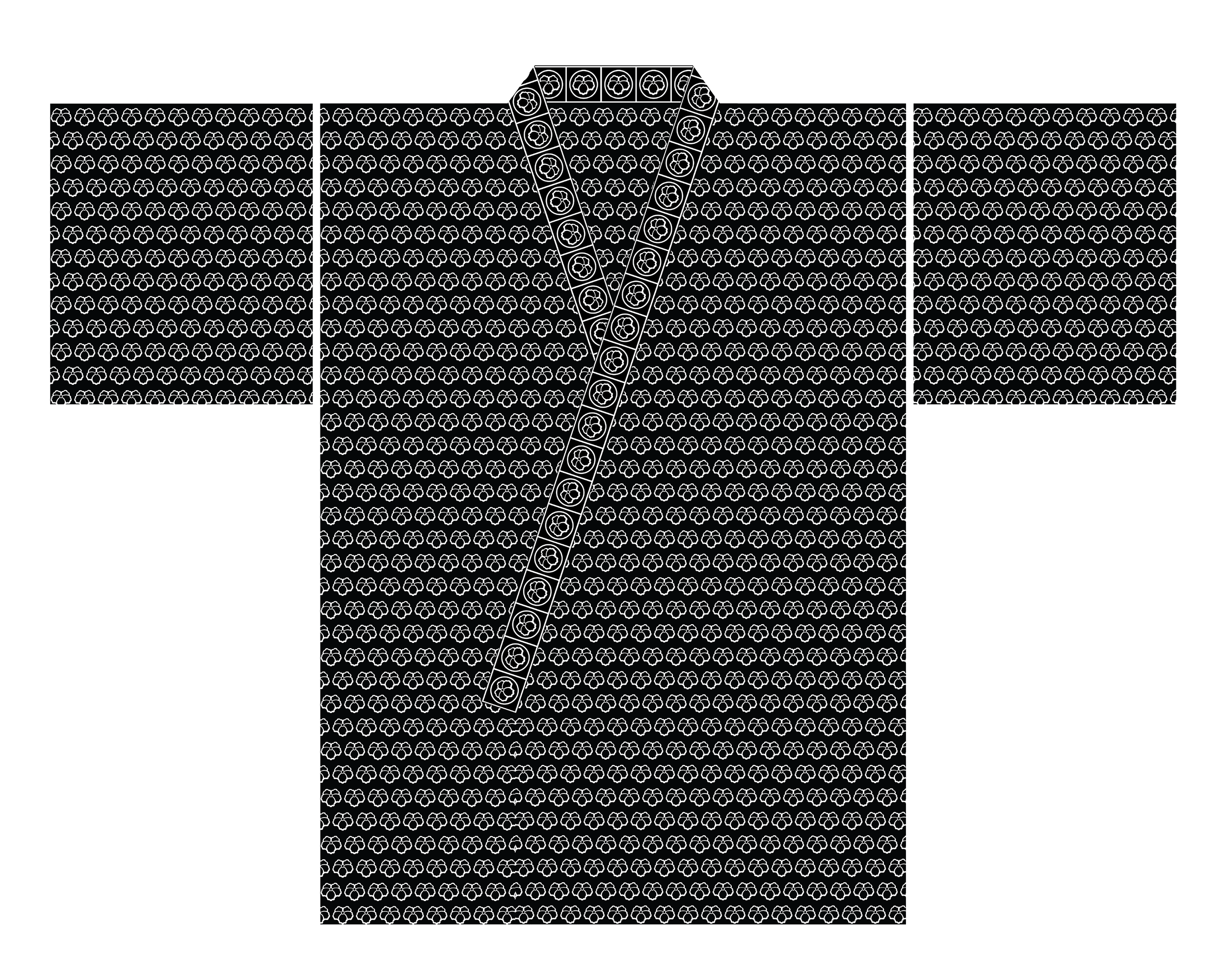

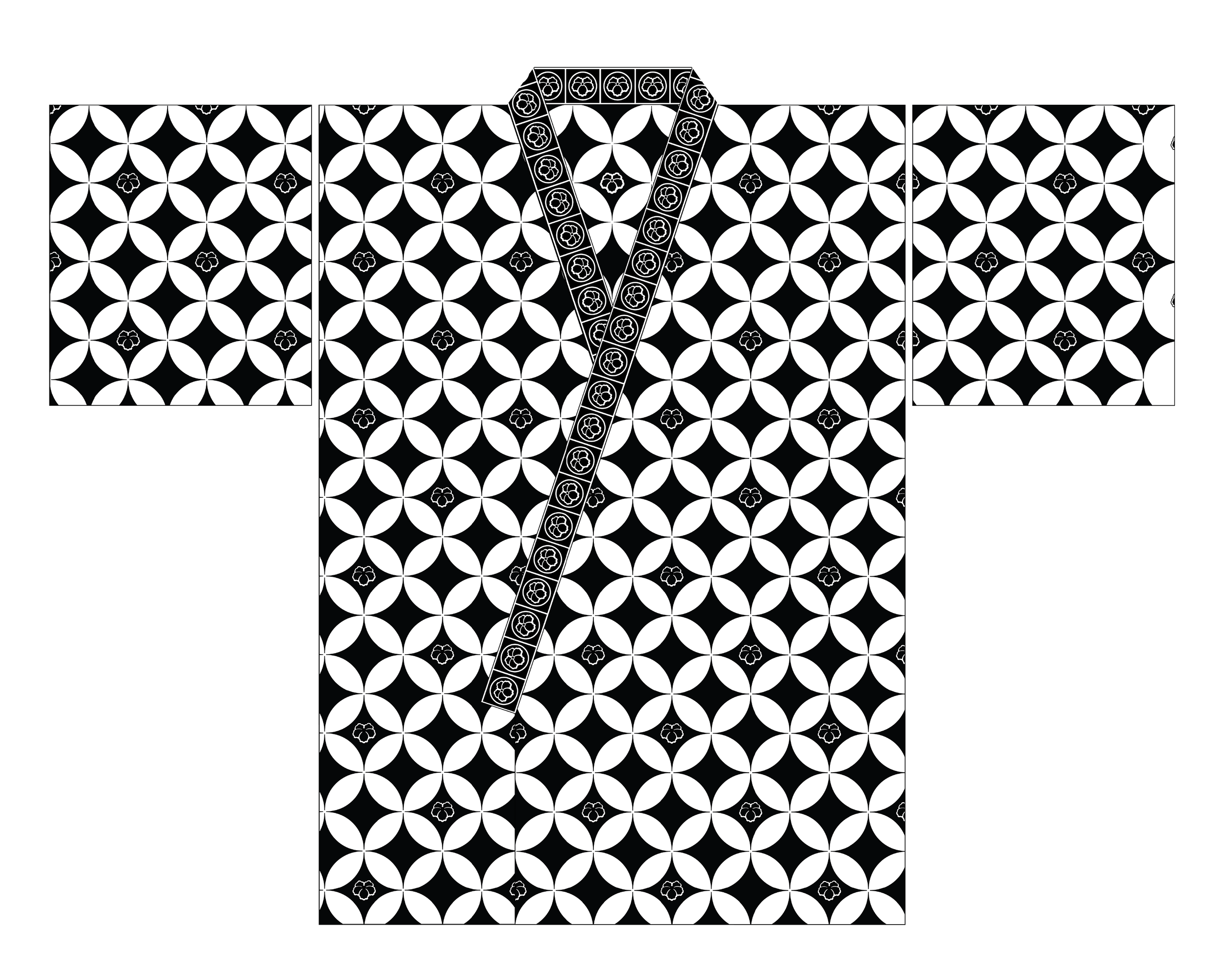

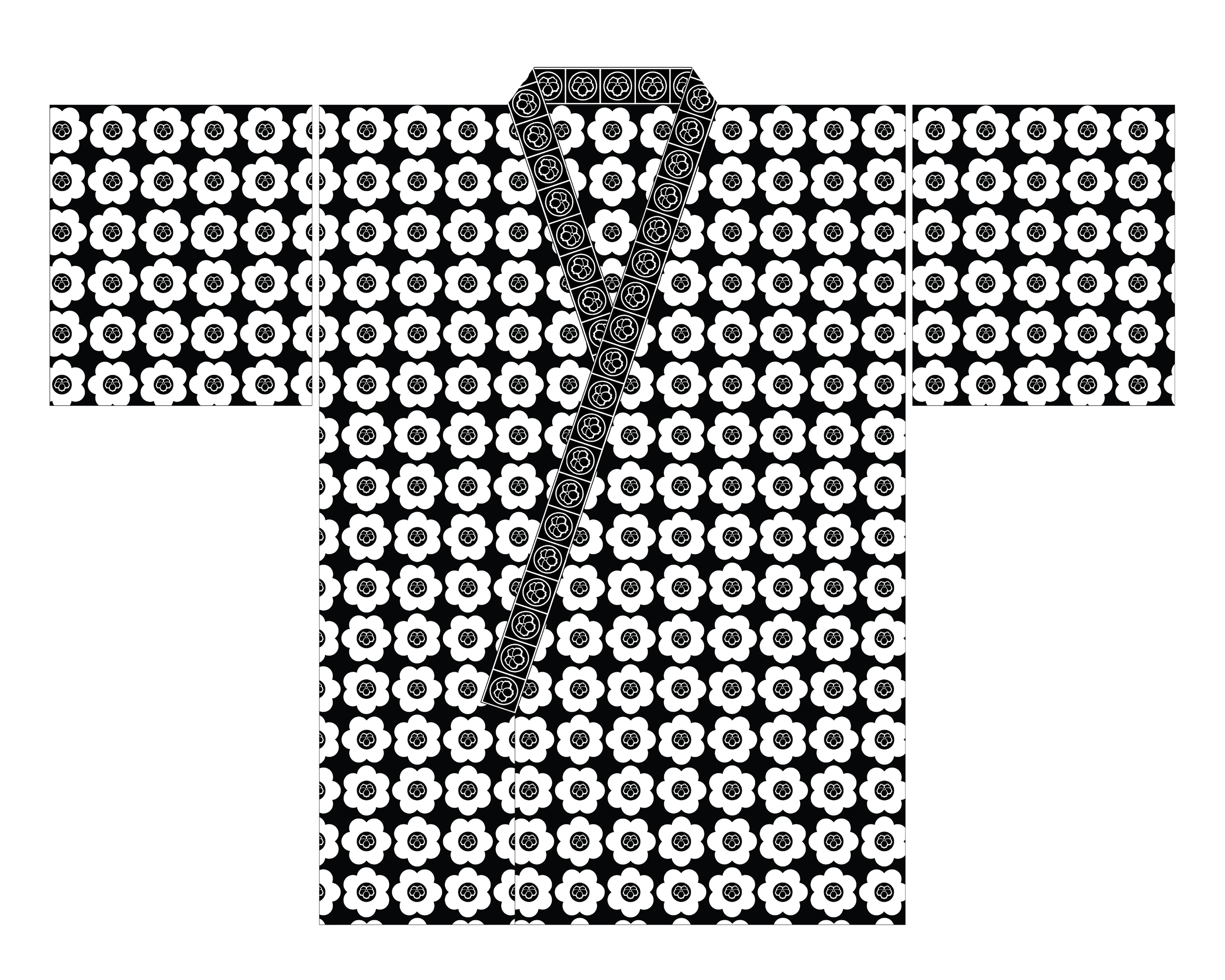

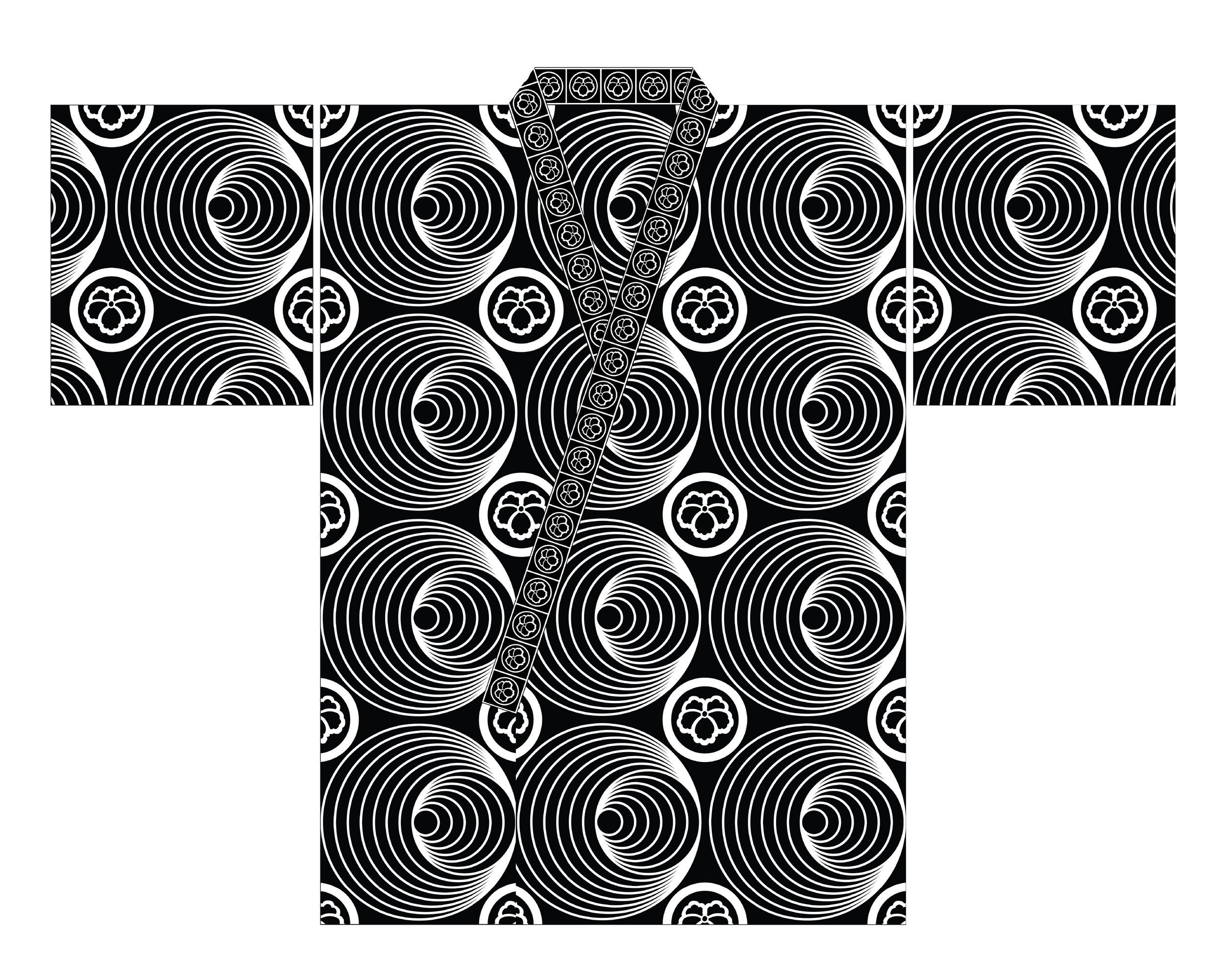

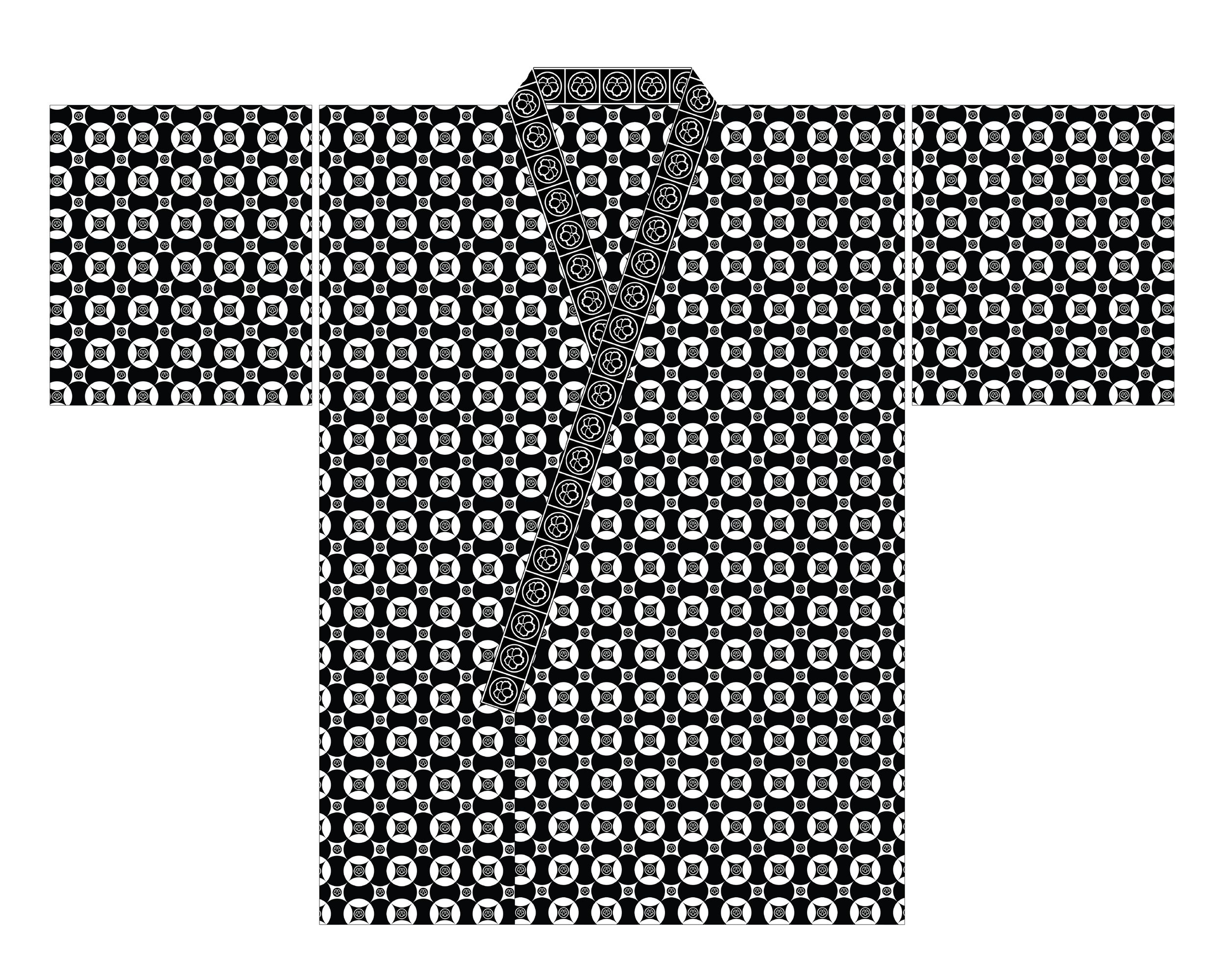

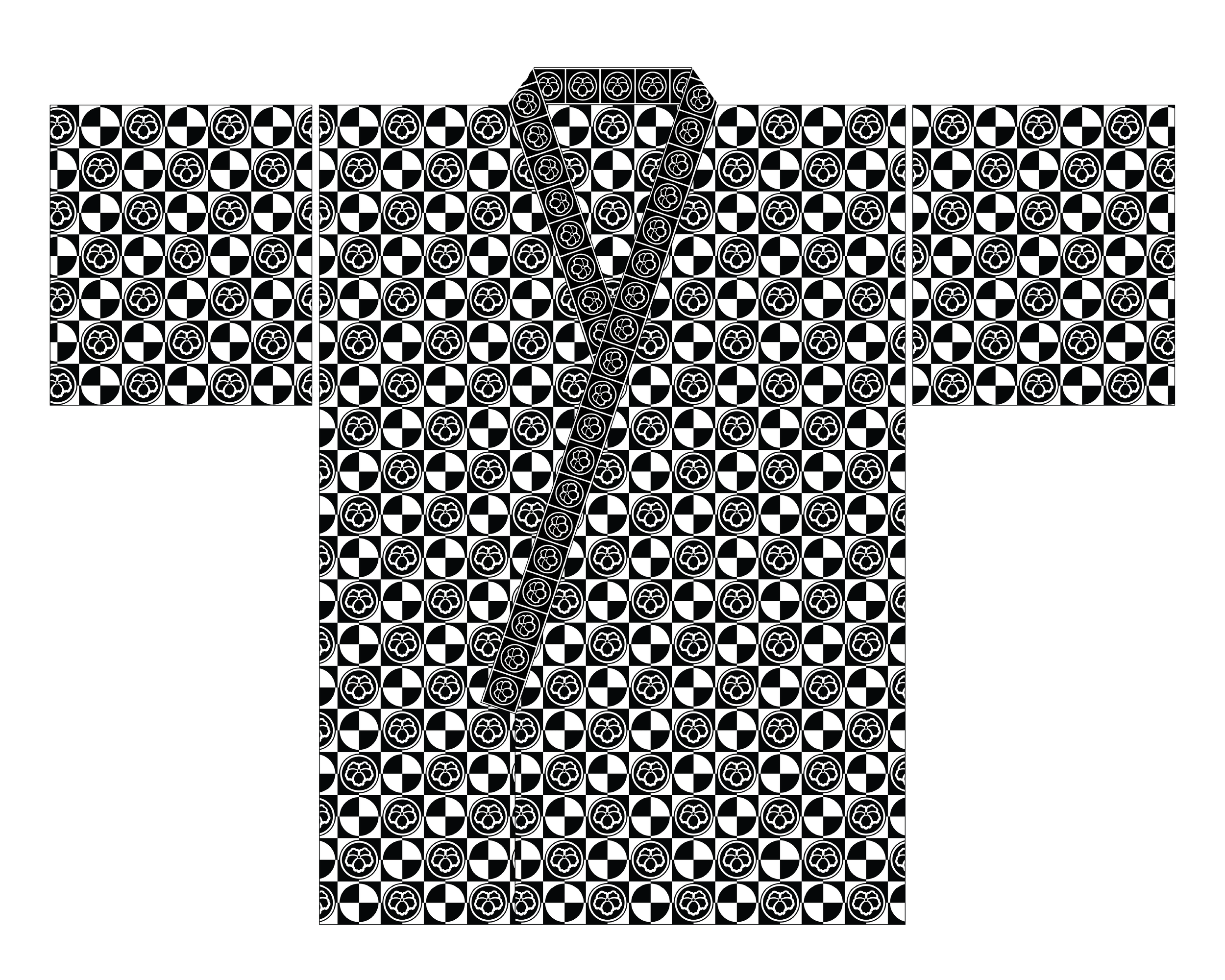

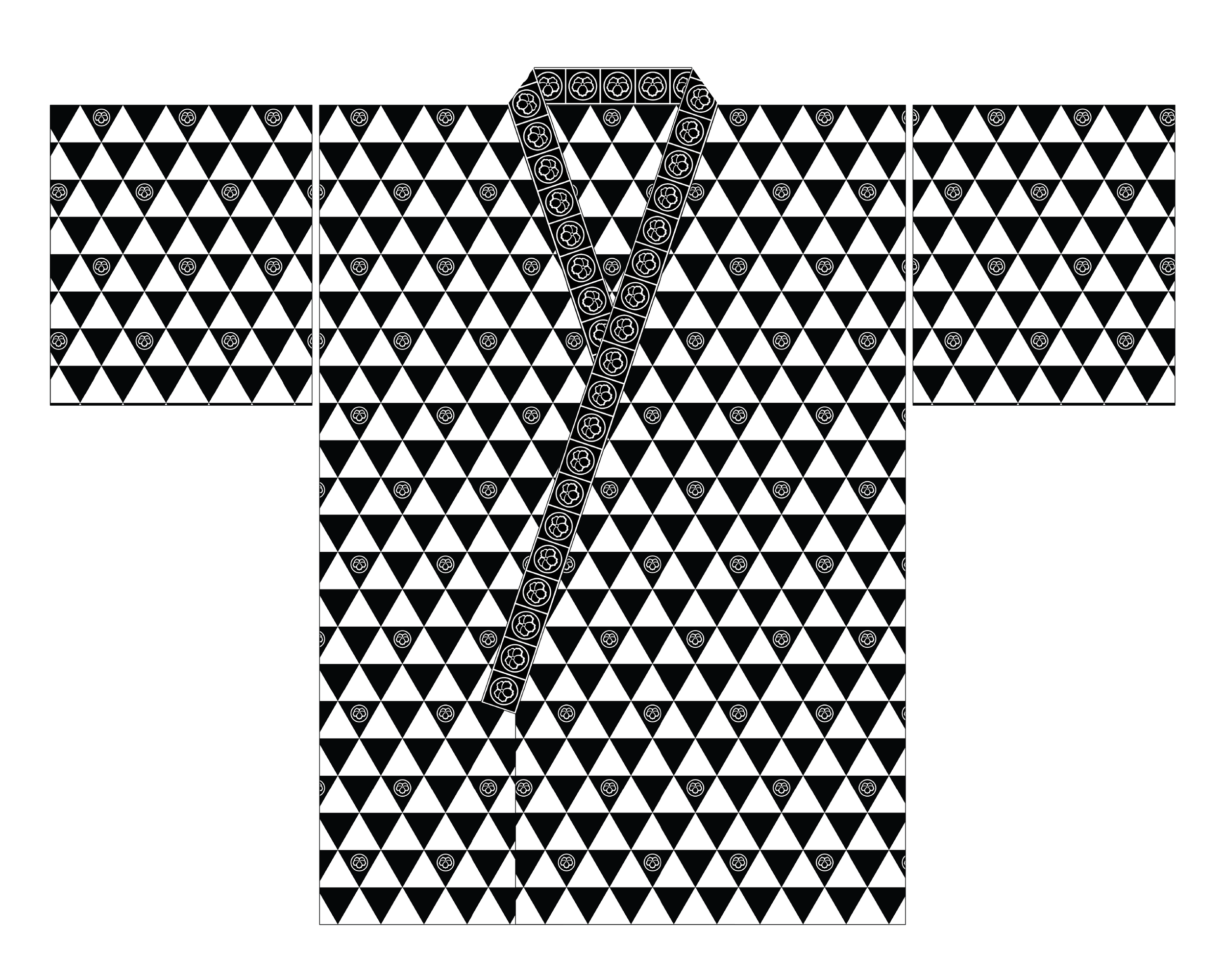

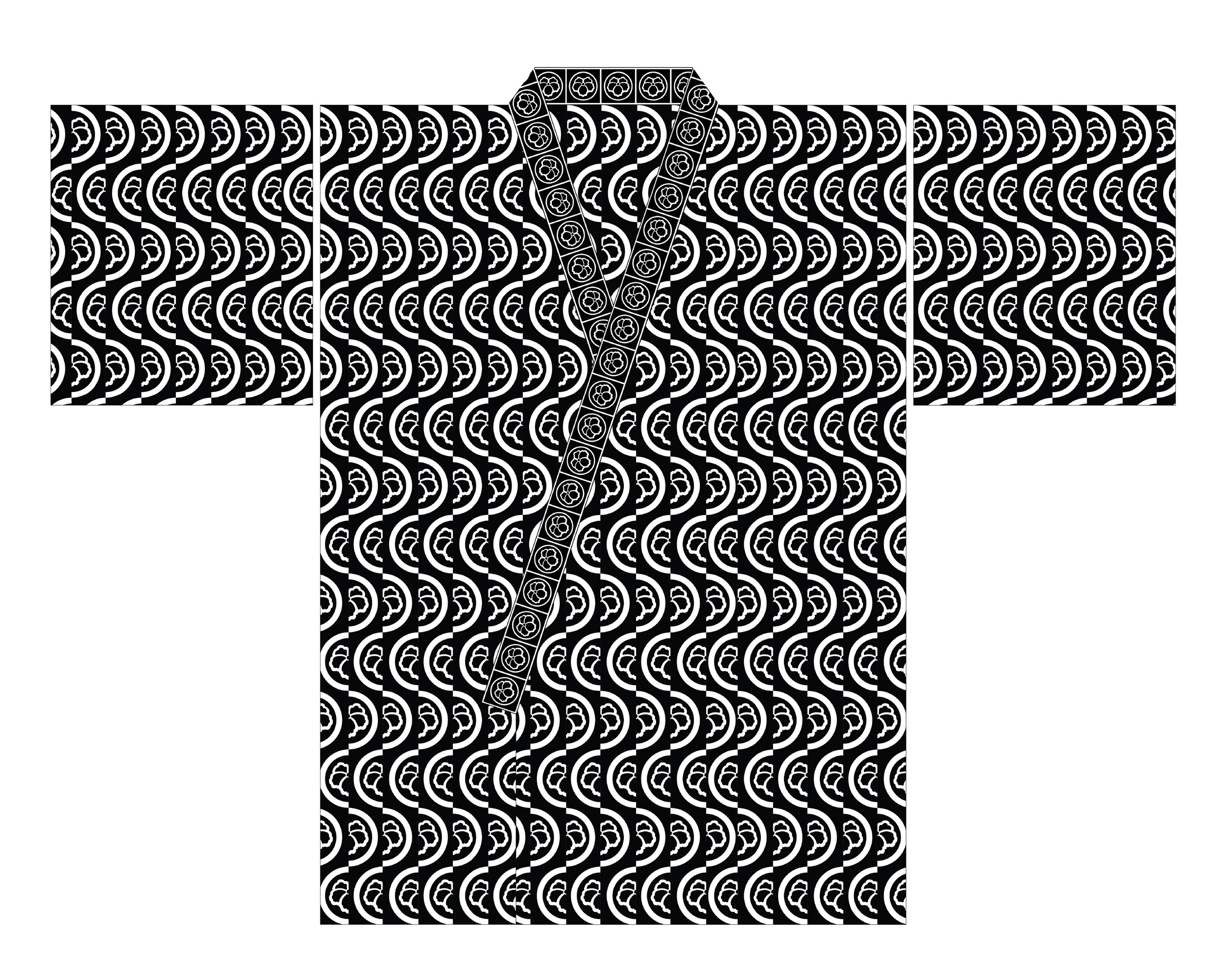

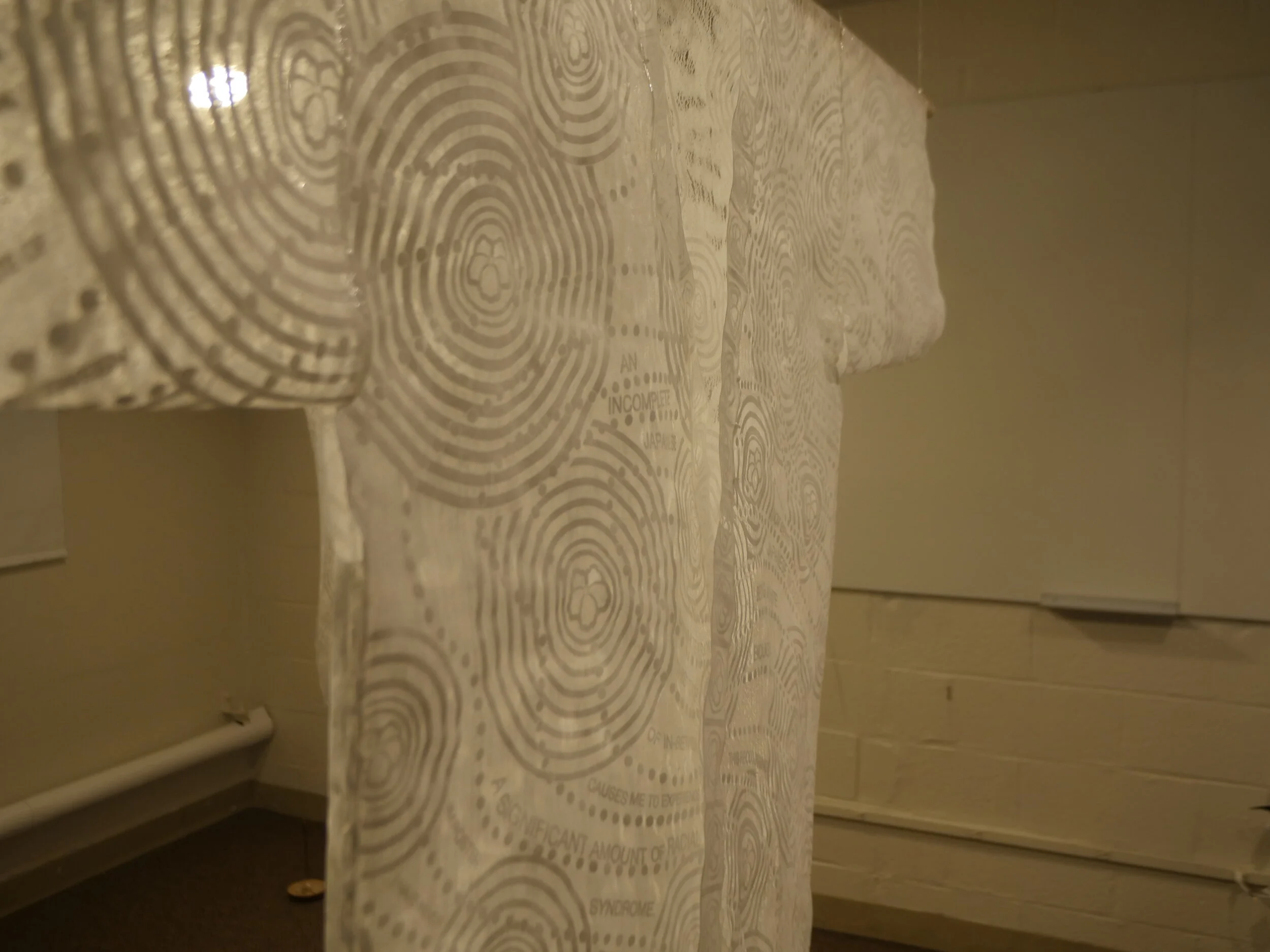

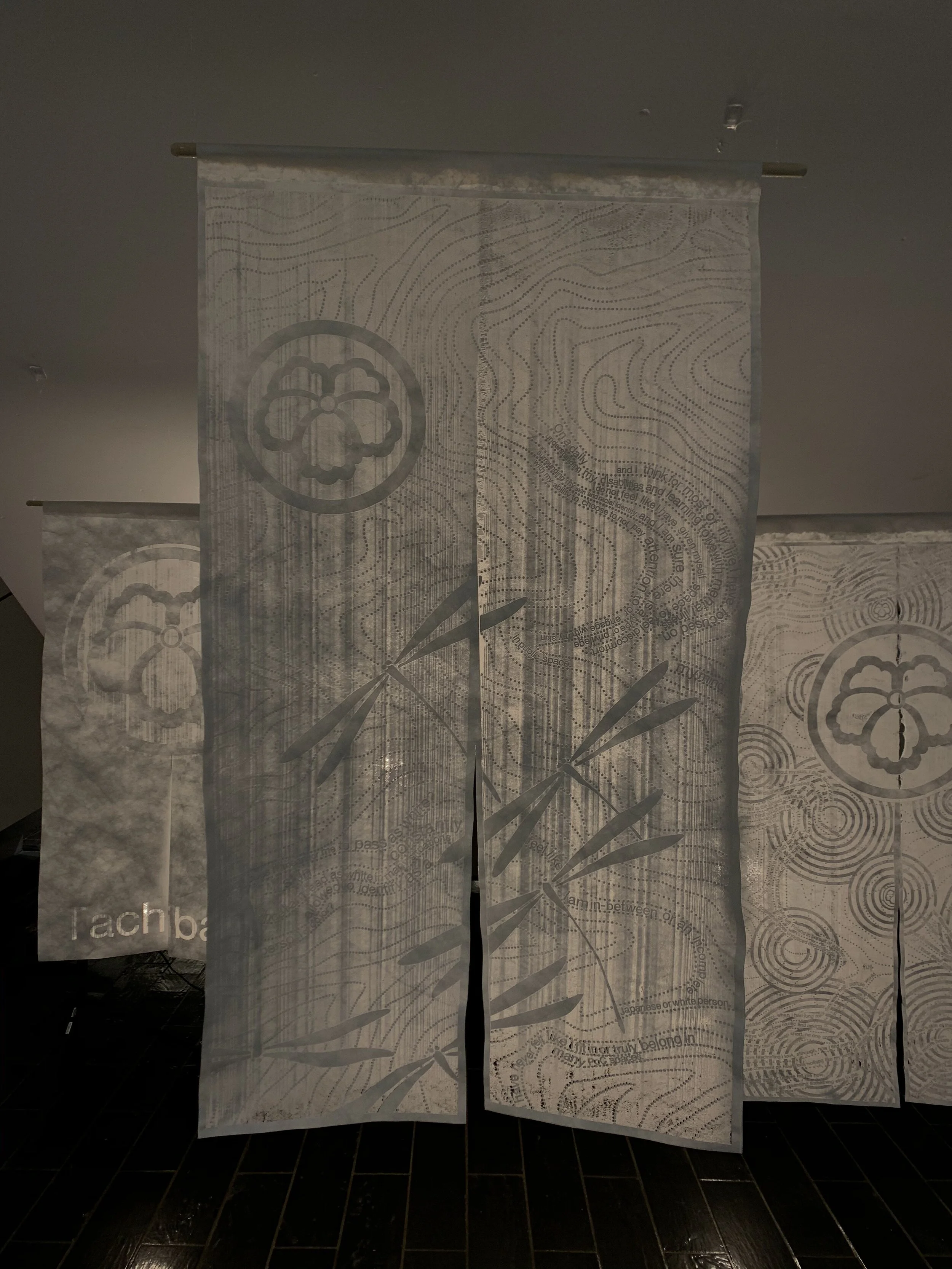

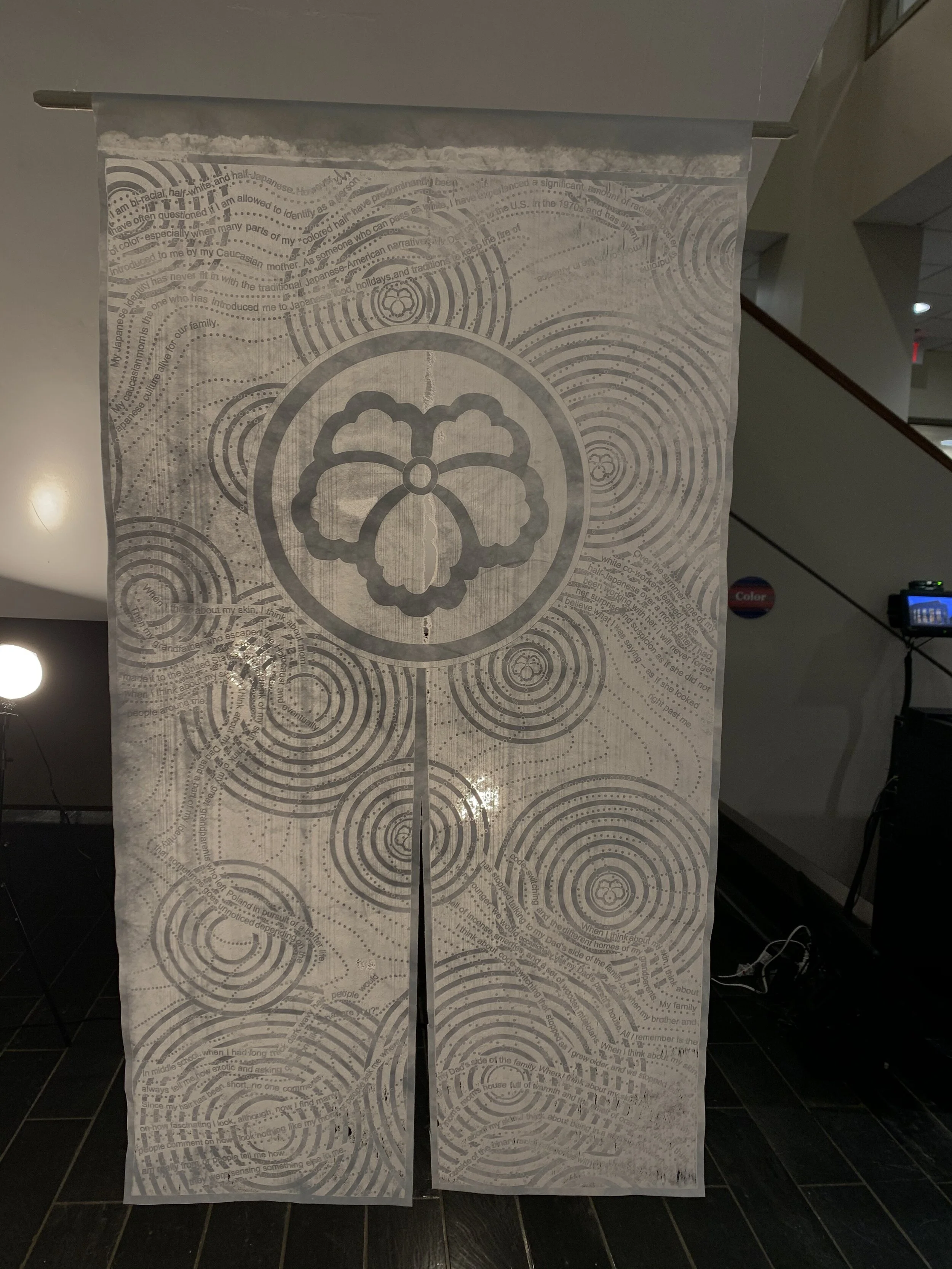

I created a skin memory installation to convey my experience of being biracial and white-passing, thinking about my skin as a boundary that often hides my Japanese heritage. I designed patterns inspired by traditional Japanese indigo dyeing techniques, incorporated the image of my family’s mon, and wove my experience of race throughout the piece. I am interested in the accumulation of patterns and how the visual designs are conversing with the text. Using the laser cutter, these designs were etched on tyvek and constructed into two happi coats (a casual Japanese garment) and three norens (curtains). I created an installation where the space was lined with diffusers filling the room with the scent of orange peels and a stick of incense burning in one corner. Interested in scent memory, the smells symbolize my grandparents' homes and their unequal presence in my life. This also creates an olfactory experience that mimics the code-switching often required of multiracial folks. I am interested in how the body becomes ghosted, the performative acts within objects, and spectators as co-producers within the work. The viewer is invited to feel close, to look beyond the beautiful objects, and to read my written experience of code-switching, the tangles of mixedness, and feeling like an imposter in my skin. I want to invite layers of spectatorship, creating a piece that tells the viewer more the longer they spend with the experience. I see this installation as a rough draft, which I will reinstall when coronavirus ends, and we have the space to build things again.

The happi coats are constructed with tyvek. Tyvek is a company; the material is more accurately a high-density polyethylene fiber, a durable synthetic material. Tyvek sits beyond the borders of art disciplines. It feels like and is not paper or fabric, and the material itself is a synthetic mixture. As a transparent white material, Tyvek performs the experience of white-passing. The material could almost pass as fabric or paper, though its texture makes it apparent that it does not belong to those categories. The material parallels discussions of mixedness, available for commercial use in 1967 (not a serious connection, though, this was the same year interracial marriage was legalized in the US), tyvek is of the contemporary moment. There is a flexibility to tyvek that speaks to the malleability of mixed-race identity, and Asian-American subjects who exist outside the bounds of black and white race relations. We are in a state of flux, cast as a high achieving model minority or an alien threat to the nation. We can not hold both these possibilities, unable to disperse the binary of good or evil.

Someone suggested I pivot to rice paper or silk, to amplify conceptual themes throughout the piece, and to further a connection to Japanese culture. This suggestion essentialized my identity to something that can be immediately legible to a white viewer. Tyvek is affordable, durable, resistant, a woven fiber, and a mixture of plastic. The material amplifies the nature of mixed-race identity that is constructed, continuing, and contemporary. There was also the suggestion that I should follow Yinka Shonibare’s intentional use of fabric to comment on the history of the garment, the kimono. I was not heard. I am not constructing a kimono. And I am not interested in discovering the linear history of the garment, which neglects to recognize the nonlinear experience of being mixed race. My gut tells me tyvek is the right material. My gut knows. Many of my multiracial Asian American friends said this piece made them feel seen; their voices are essential. I am working to move beyond the work of representation towards creating installations that invite a sensual experience, exploring how the body haunts objects without making my identity into a spectacle for passive consumption.

Most importantly, tyvek is an exciting material. Excitement invites a mode of study grounded in pleasure, not exhaustion, and encourages a politics of refreshment. Descartes’s silly mind-body distinction explains why I have been conditioned to not trust a sensation that is embodied. My mind is not superior. My body thinks and theorizes before my brain has the language to articulate. I imagine a mode of study where my gut precedes my mind; my gut is a thinking thing. The primacy of writing as the dominant mode of academic thinking can be frustrating. This idea that writing is thinking and thinking is writing does not always account for the ways in which my body thinks without words. What is the repertoire of embodied excitement? Sometimes words fail to communicate a gut instinct that the body knows before one has the language to justify embodied choreography. Unlike excitement, joy feels like a choice, something I can control through work and medication. Excitement falls in my gut. Excitement feels like a spark beyond joy, a sharp intensity. Excitement is an opening, an animating appetite to wander, get lost, and arrive.

Fall 2019 Installation

Fall 2019 Installation

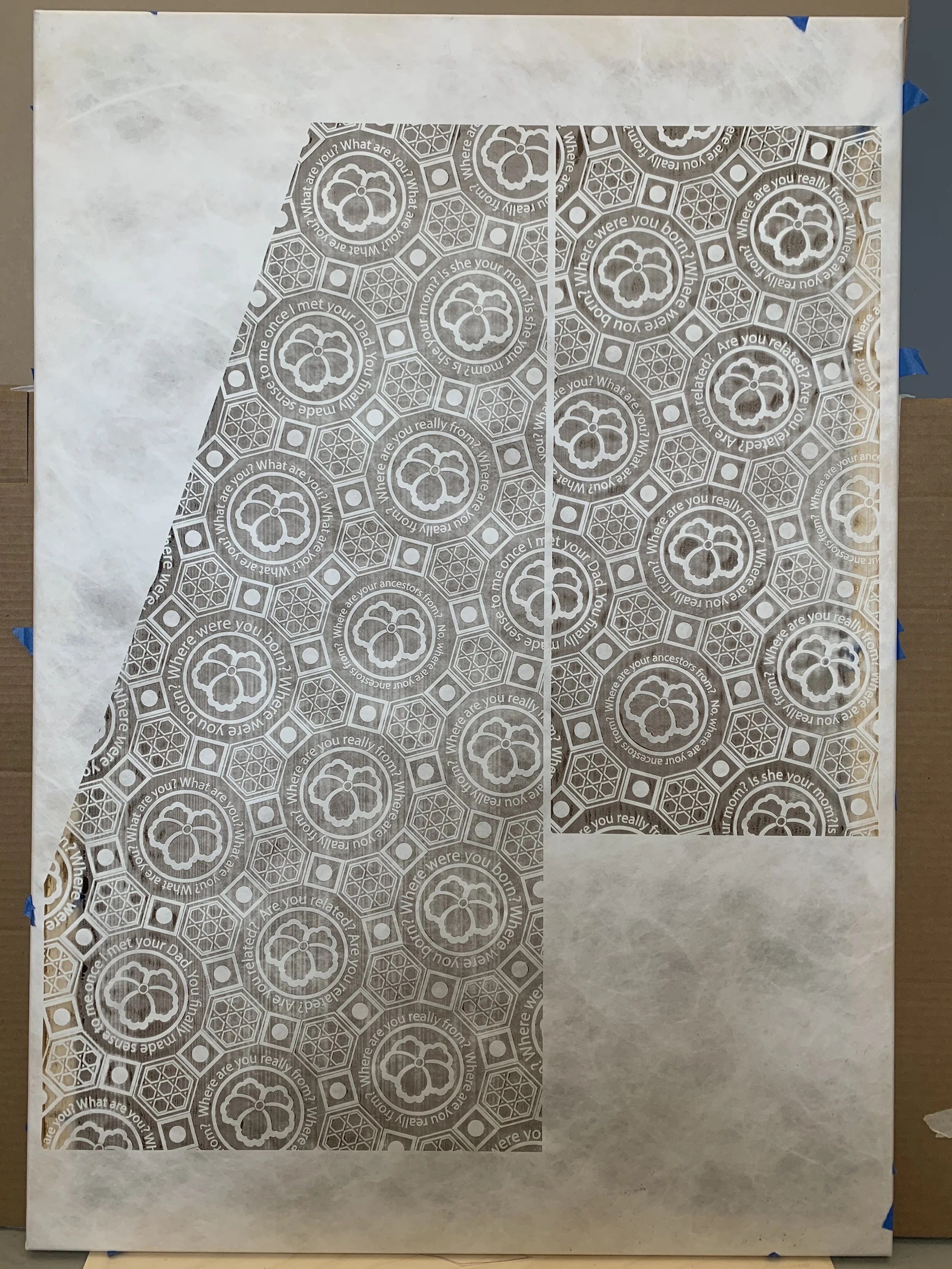

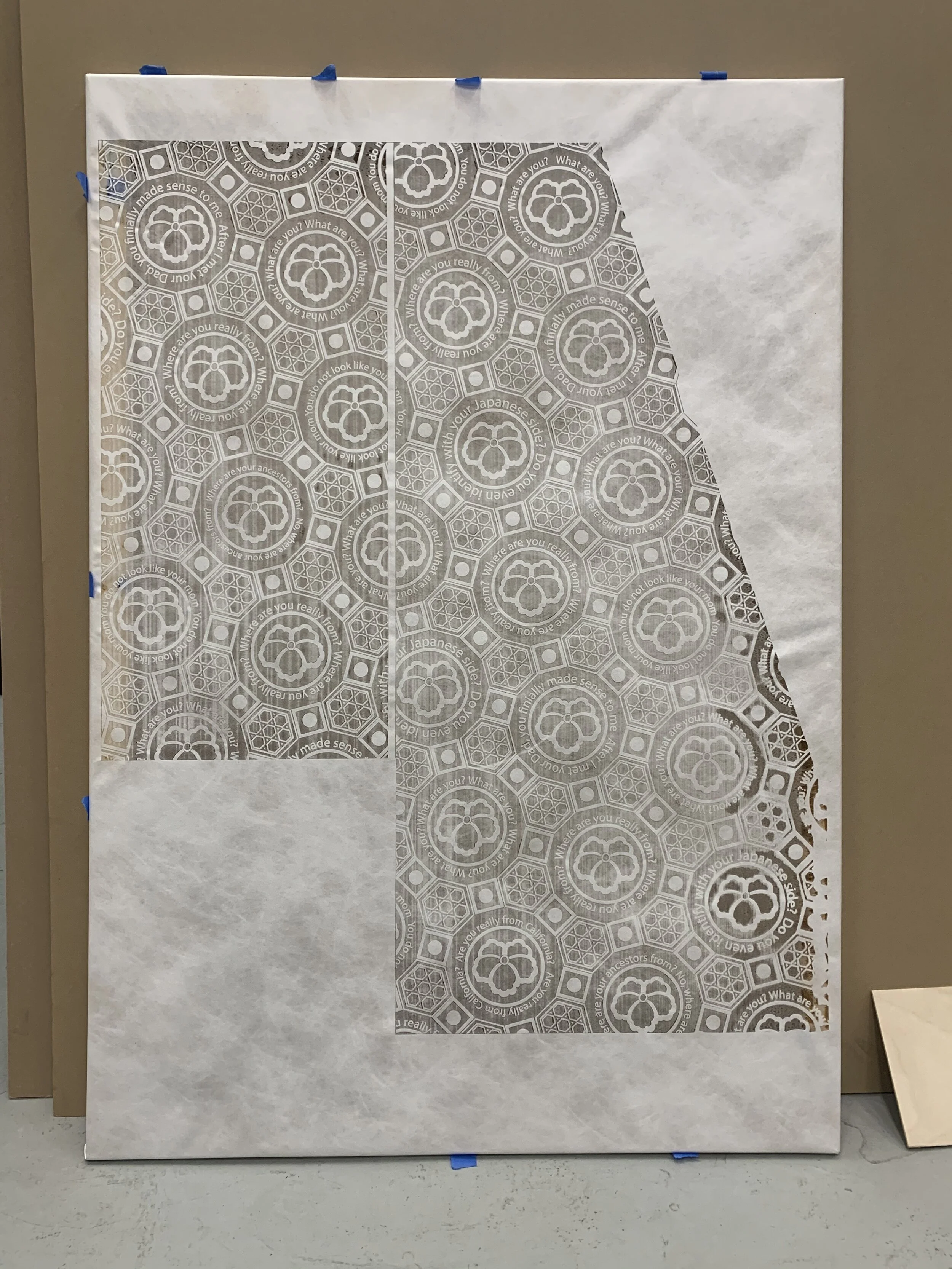

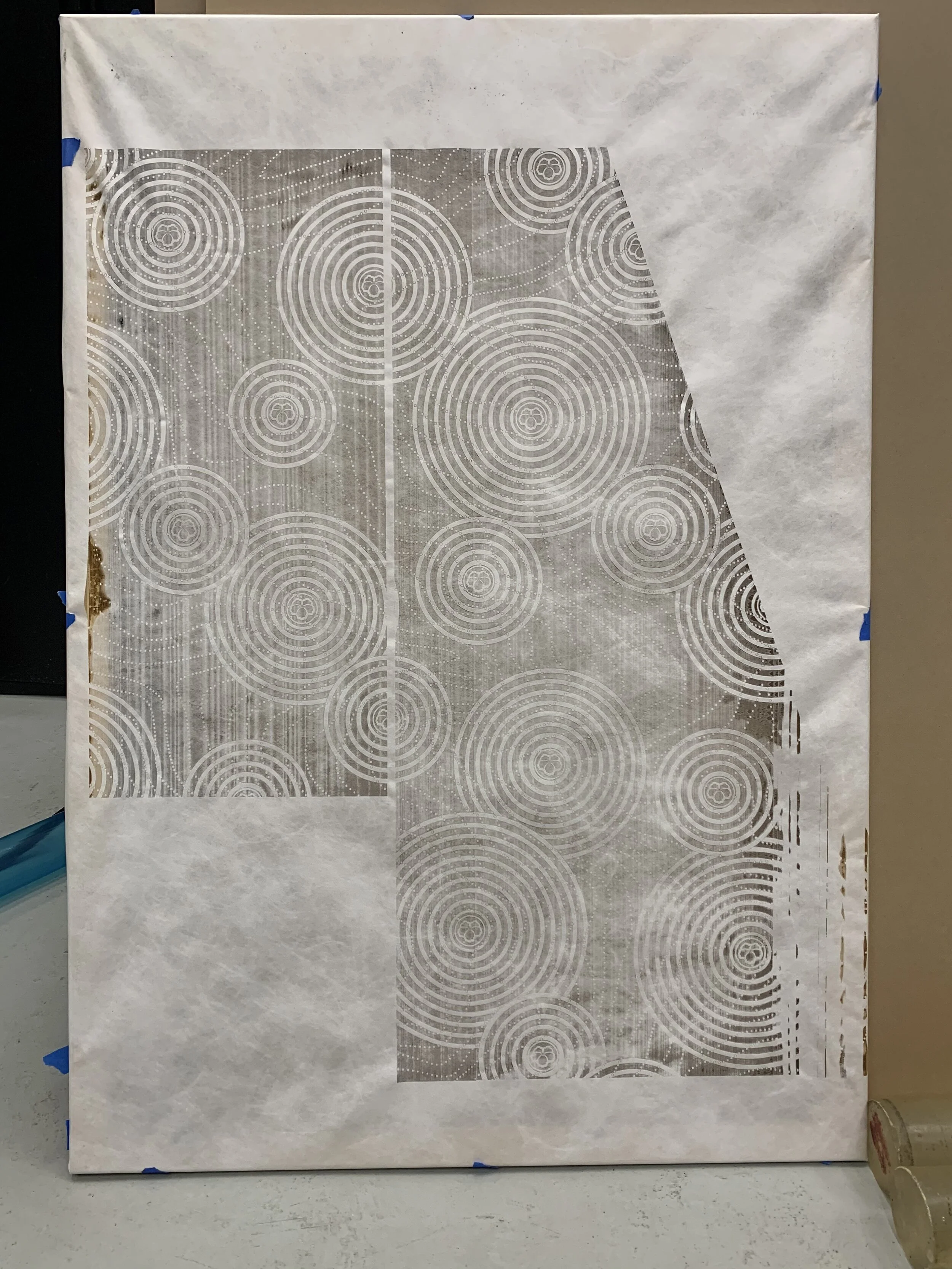

Tyvek Detail

Tyvek Detail

Tyvek Detail

Tyvek Detail

Tyvek Detail

Tyvek Detail

Tyvek Detail

Tufts Library Installation February 2020

Three Norens Detail

Noren Detail

Installation Plan

It all begins with an idea. Maybe you want to launch a business. Maybe you want to turn a hobby into something more. Or maybe you have a creative project to share with the world. Whatever it is, the way you tell your story online can make all the difference.

Soundscape

Noren (Curtains) 2019

Noren (Curtains) 2019

Noren (Curtains) 2019

Rough Draft, 2019

Rough Draft, 2019

Process Documentation